Key Words :

By chance, Texture, Fluid, Organic

Dasine, Simplicity, Folklore

Dadaism

What draws me to Dadaism is its bold questioning of what art can be. The Dadaists were not simply being nonsensical for the sake of it—they were making a point. They challenged the very definition of art, using chance operations and found objects to push boundaries. Beneath the humor and absurdity was a profound inquiry into the role of art in a modern, war-torn world. This became especially urgent during and after World War I, as Dada spread to New York, Paris, and beyond.

I love the playfulness and wit in Dada—it brings a sense of joy and freedom. But even more than that, I admire how it dares to experiment, to question, to break rules. It reminds me how vital it is for artists to be sensitive to the world around them. In many ways, artists are like doctors or therapists for society—they observe, interpret, critique, and ultimately help keep society honest and healthy through their creations. They address politics, expose injustice, and offer new perspectives.

Another reason I appreciate Dadaism is its celebration of life’s absurdities—it brings out the fun and unpredictable aspects of being alive.

Jean Arp

I first came across Jean Arp’s work online while searching for inspiration. Born Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp (German: [aʁp]; 16 September 1886 – 7 June 1966), Arp was a German-French sculptor, painter, and poet, and a key figure in both the Dada and abstract art movements. His sculptures immediately captivated me—they were both elegant and uncanny, with flowing organic shapes, rich textures, and an intriguing use of materials.

At the time, I was at a turning point in my own creative process, reflecting on how to move forward from Unit 1. I had been deeply immersed in researching themes of existence and life, collecting natural objects like stones and bones through mud larking. These objects became part of my philosophical inquiry into life and death, and I found myself searching for a way to express those ideas more deeply.

One of the most meaningful discoveries I made about Arp was his embrace of chance during the First World War. He famously explored the idea that if you drop pieces of paper and let them fall where they may, the final composition is determined not by the artist, but by chance itself. That surrender of control fascinated me. It reminded me of life—constantly shifting, full of unpredictable possibilities. Why not let that same randomness guide the process of making art?

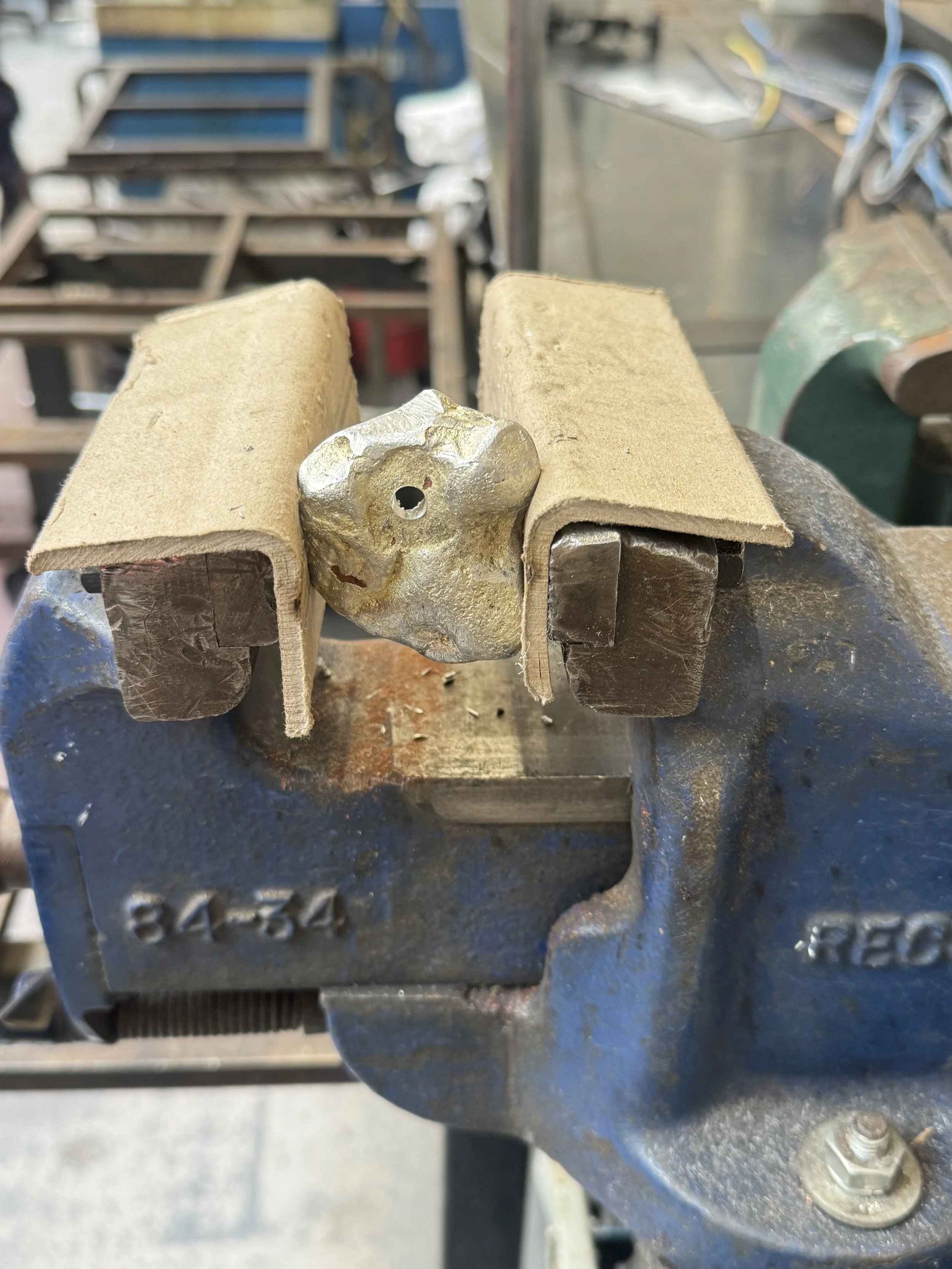

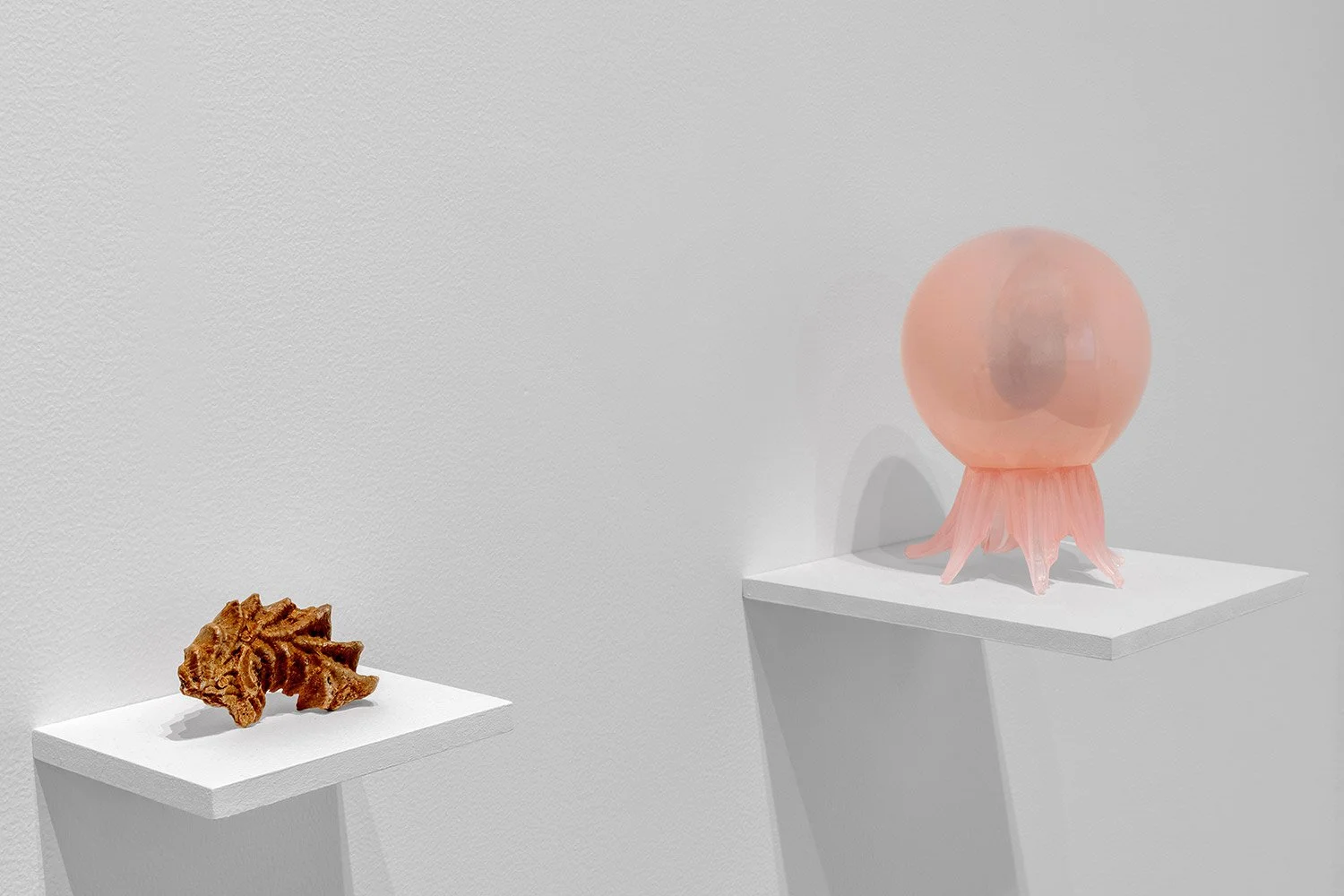

I was particularly inspired by his work “According to the Laws of Chance.” shows Arp playing with random composition, in this case dropping painted pieces of paper onto a surface. It sparked the idea that I could combine chance and science—particularly within the etching process, which I see as a slow, evolving journey that mirrors the cycles of cell division and life formation. In this way, my work becomes not just a representation of life, but an act of life itself—shaped by time, material, and the unexpected. I also try to do some sculpture like Jean Arp, I discussed with the technical instructor in Foundry work shop, she give me the idea to use balloon crate this fluid organic shape, but I don’t like the result, I guess I don’t like the shape crate by my own, I prefer more natural organic shape.

Jean Arp sculpture in Tate modern

Use balloons to make a shape

Constellation According to the Laws of Chance in Tate modern

Cover balloons with plaster

According to the Laws of Chance, 1933

Connect bottom and each part

Final work

Martin Heidegger

Over time, I began to understand that my work wasn’t just about the objects I collected—it was about the form, the essence, and the materiality they embodied. This shift in perspective was largely influenced by my reading of Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time. In it, Heidegger critiques traditional existentialism for being overly concerned with the consequences of existence, rather than existence itself. He introduces the concept of “Dasein”, a German term meaning “being-there,” to describe the unique, conscious experience of being human.

For Heidegger, Dasein is about being actively and thoughtfully engaged with the world—caring for it, while remaining aware of the fragility and impermanence of that engagement. It’s a recognition that the world exists before the self, and that the self is in a constant process of becoming. In contrast, inauthentic Dasein refers to losing oneself in the routines and expectations of everyday life—absorbed in the anonymous voices of “they” and “them.”

This concept deeply resonated with me. It pushed me to think more consciously about materials and form, and how they can express not just external themes but the experience of being itself. That’s why I began casting a hagstone I found while mud larking, experimenting with different materials as a way to explore the body of existence. This led to an idea: what if I let life happen on a zinc plate—allowing chance, time, and transformation to take over?

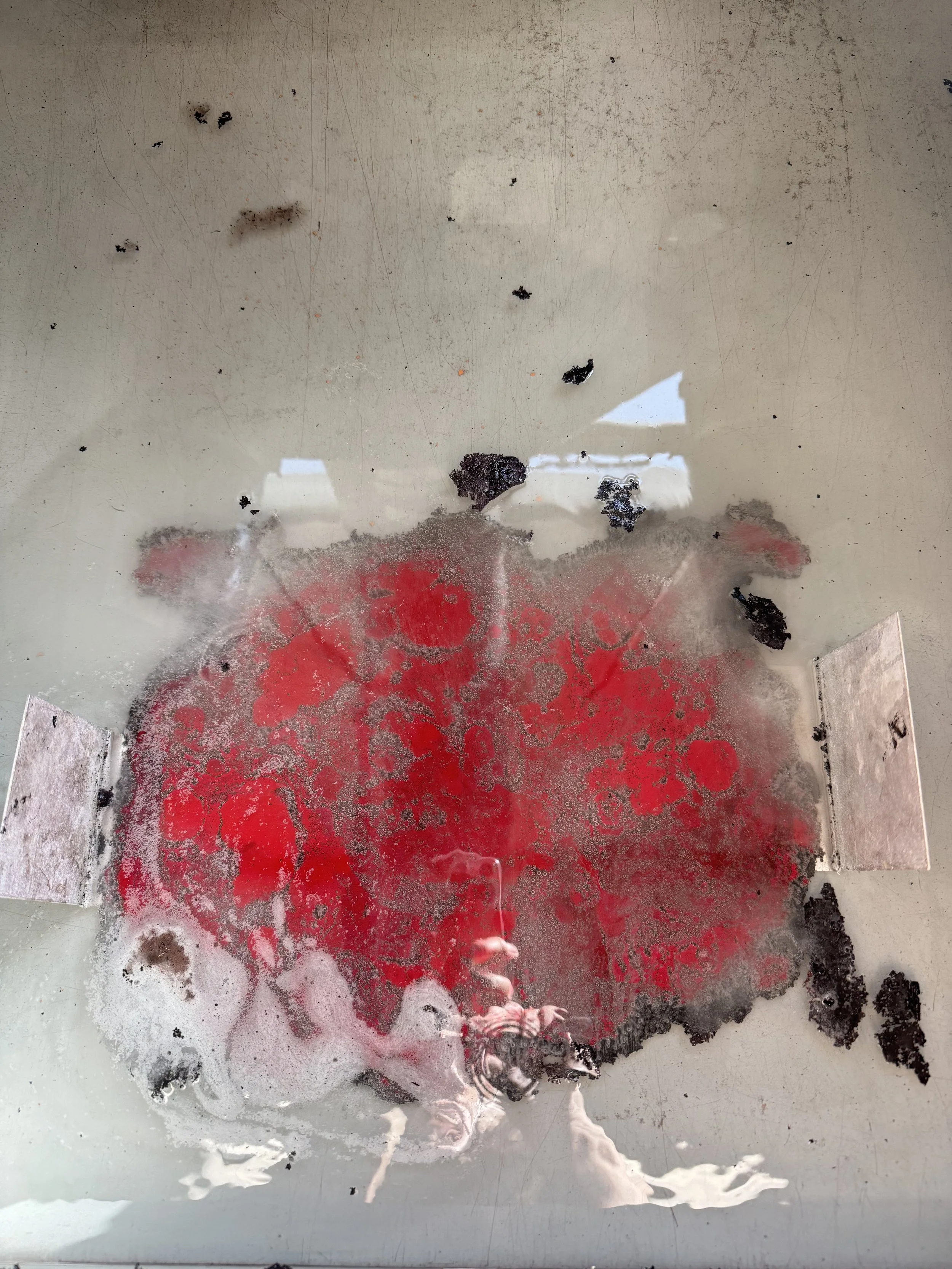

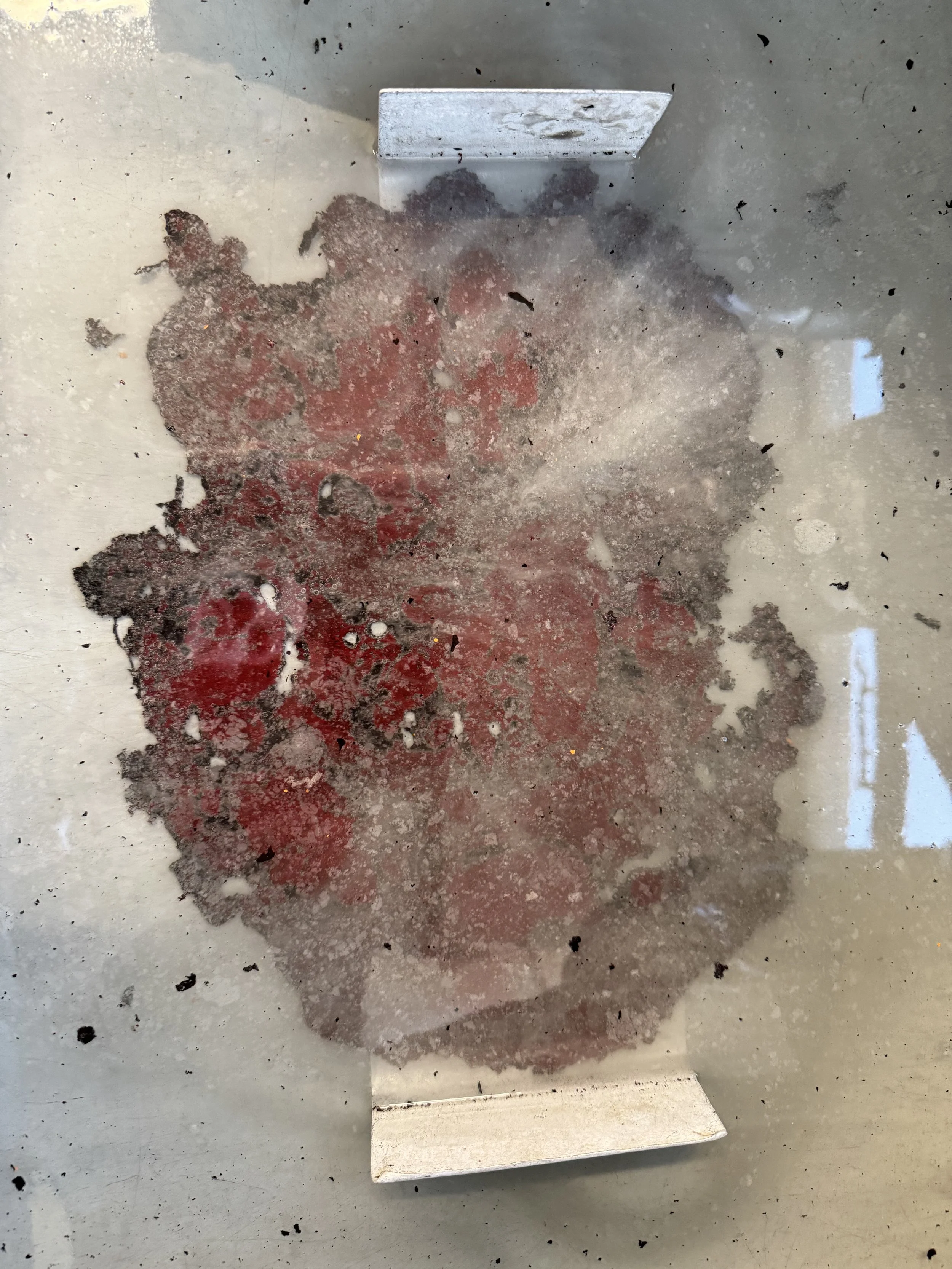

That moment sparked the foundation of my Unit 2 project. I decided to dissolve a zinc plate, letting chance shape its surface over time, much like life itself—unpredictable, shifting, and alive.

Being And Time, Martin Heidegger

Taoism

My inspiration always stems from the culture I grew up with. I’m particularly drawn to Tao, the philosophy that underlies all existence, which teaches that everything originates from the boundless resources of the universe. Significant movements in early Taoism disregarded the existence of gods, and many who believed in gods thought they were subject to the natural law of the Tao, in a similar nature to all other life. Roughly contemporaneously to the Tao Te Ching, some believed the Tao was a force that was the "basis of all existence" and more powerful than the gods, while being a god-like being that was an ancestor and a mother goddess.

Early Taoists studied the natural world in attempts to find what they thought were supernatural laws that governed existence. Taoists created scientific principles that were the first of their kind in China, and the belief system has been known to merge scientific, philosophical, and religious conceits from close to its beginning.

Taoist sense as an enigmatic process of transformation ultimately underlying reality.Taoist ethics vary, but generally emphasize such virtues as effortless action, naturalness, simplicity.

The Tao (or Dao) is hard to define but is sometimes understood as the way of the universe. Taoism teaches that all living creatures ought to live in a state of harmony with the universe and the energy found in it. Ch’i, or qi, is the energy present in and guiding everything in the universe. The Tao Te Ching and other Taoist books provide guidelines for behavior and spiritual ways to live in harmony with this energy. However, Taoists do not believe in this energy as a god. Rather, there are gods as part of the Taoist beliefs, often introduced from the various cultures found in the region known now as China. Like all living things, these gods are part of the Tao. Taoist temples, monasteries and priests make offerings, meditate and perform other rituals for their communities.

One of the main ideas of Taoism is the belief in balancing forces of yin and yang. These ideas represent matching pairs -- light and dark, hot and cold, action and inaction -- which work together toward a universal whole. Yin and yang show that everything in the universe is connected and that nothing makes sense by itself.

Tao Te Ching, Lao Tzu

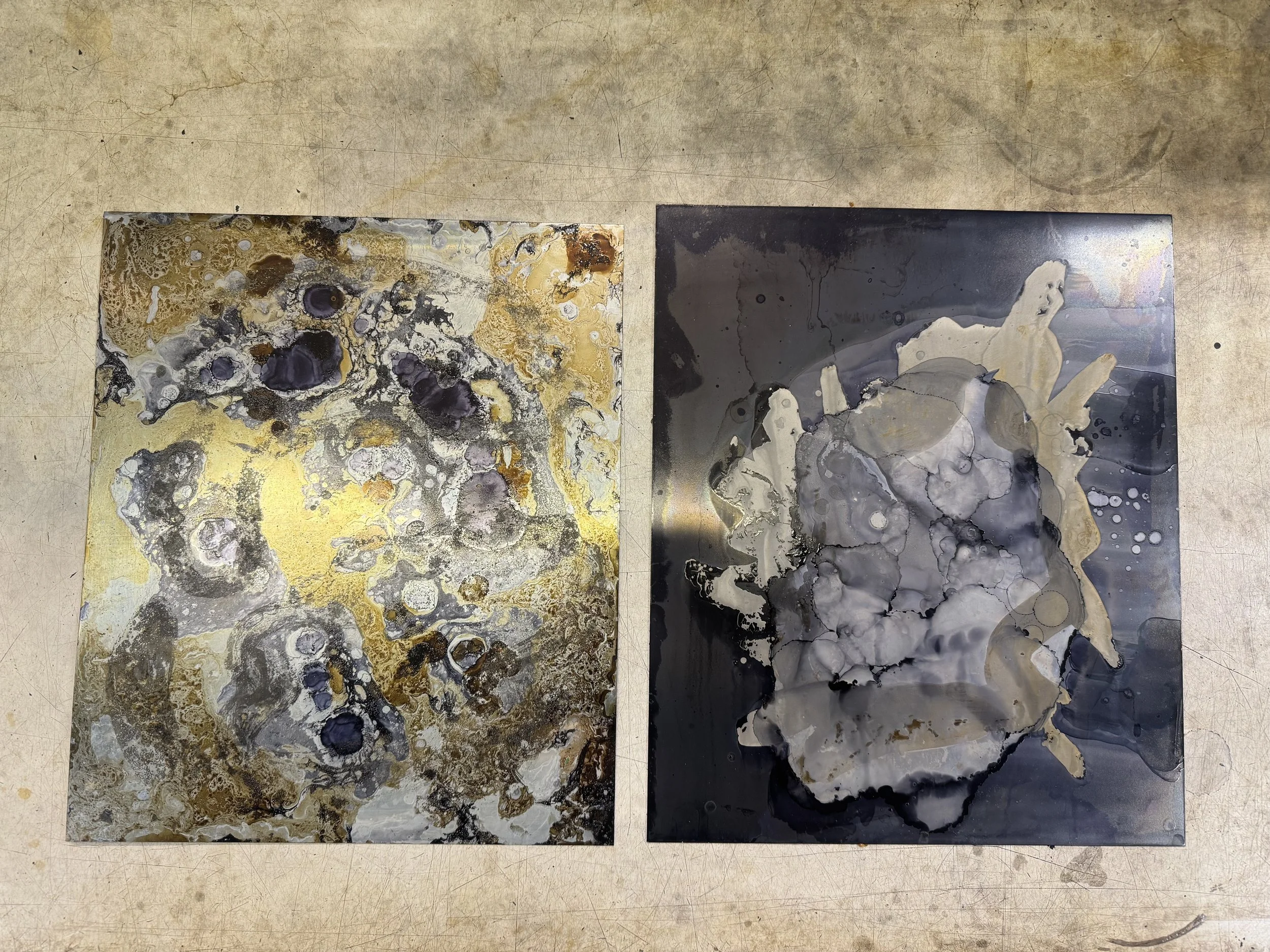

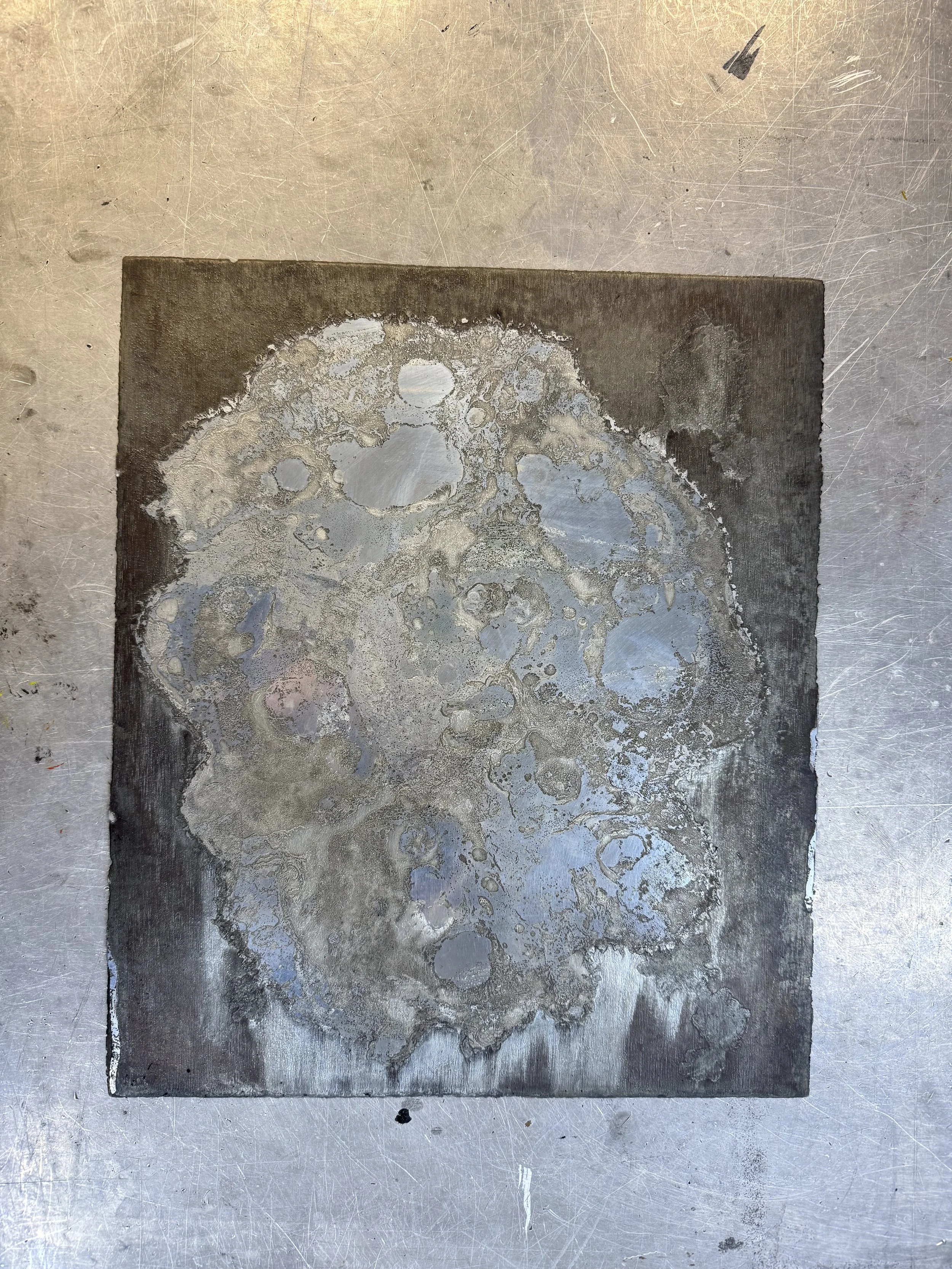

Process of Primo series

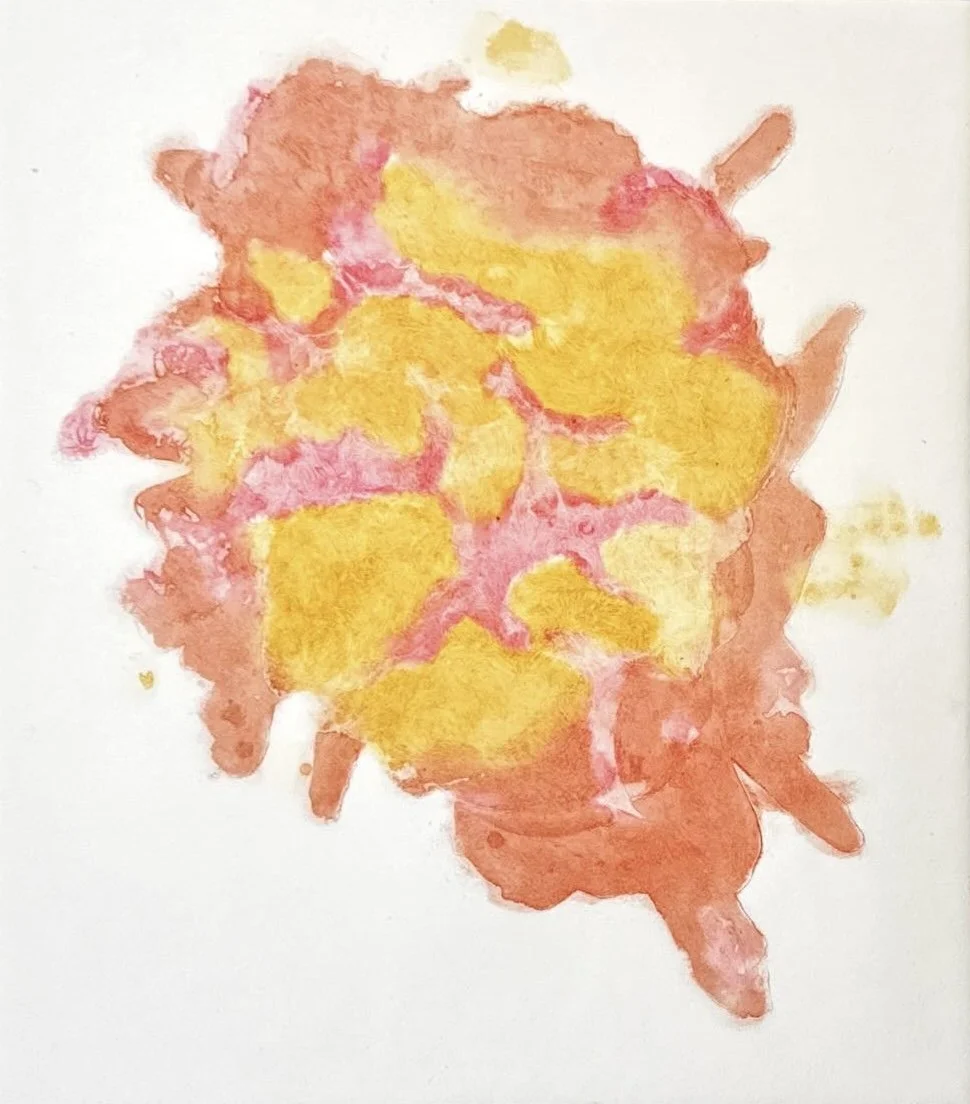

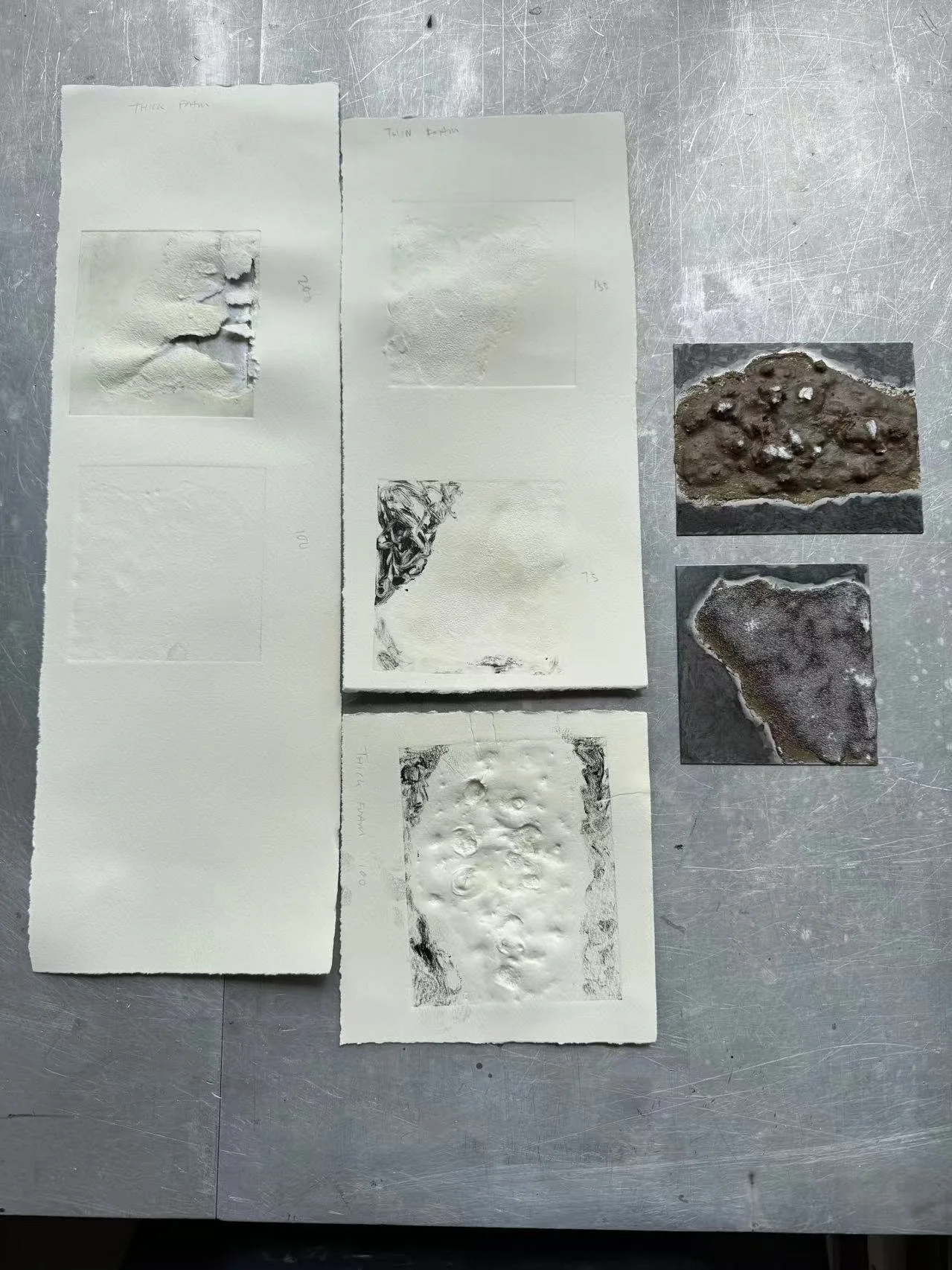

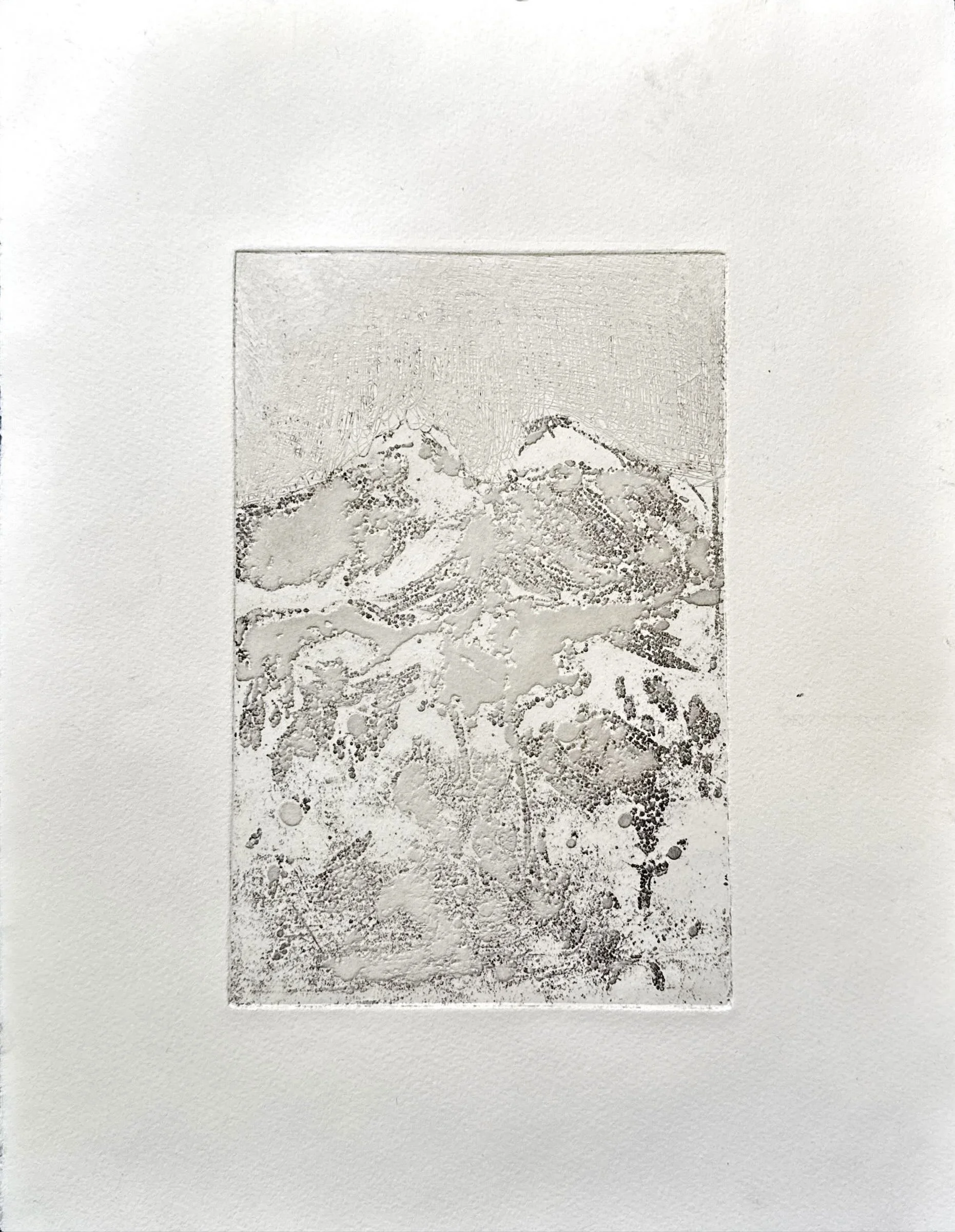

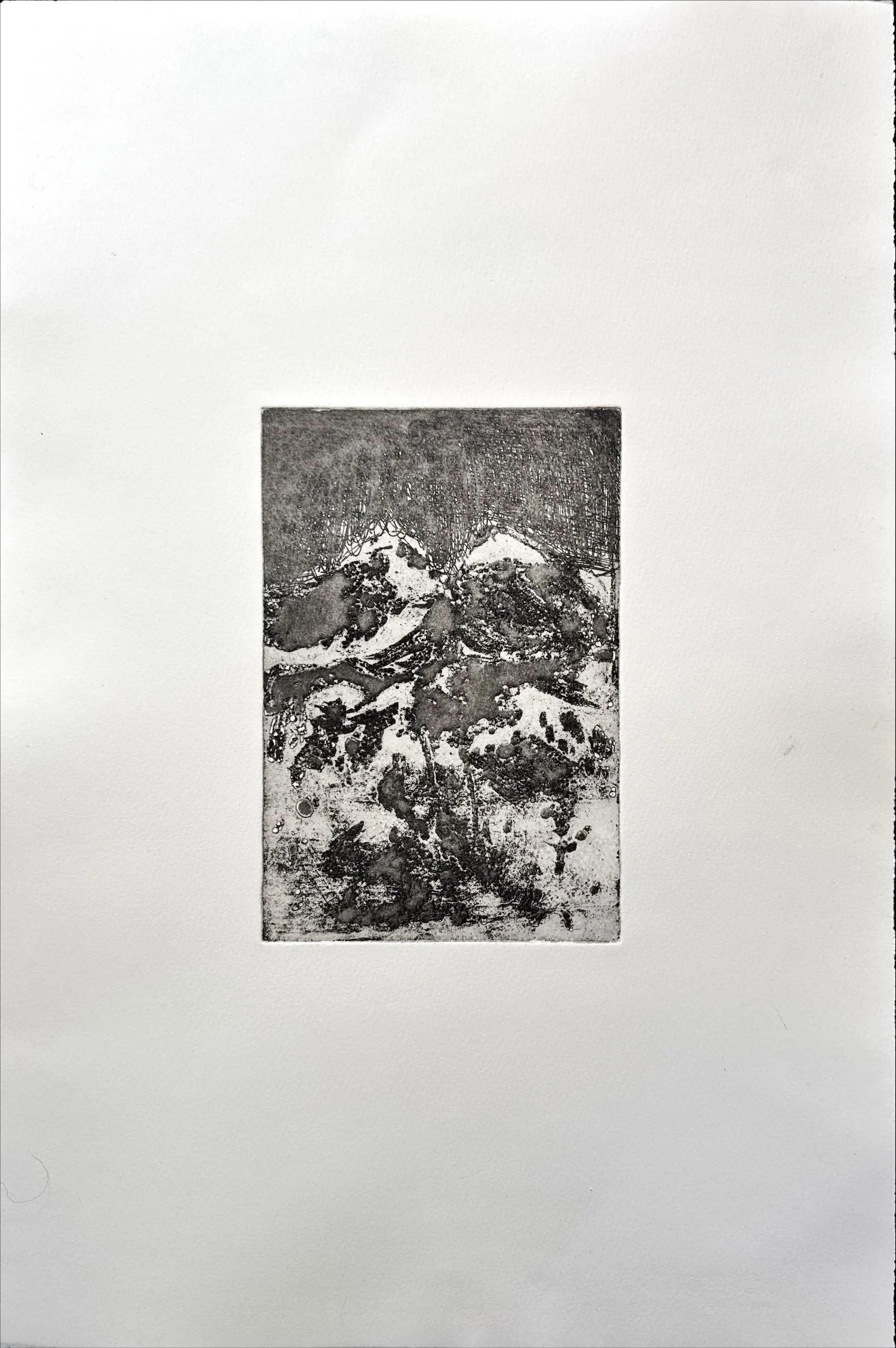

I drew inspiration from Dadaism and Jean Arp’s concept of chance, as well as the philosophies of Martin Heidegger and Taoism. My intention was to create an etching that captures the full arc of life—from beginning to end—as a continuous, transformative process. I used chemical reactions on the plate to symbolize the origins of life, gradually allowing it to dissolve until the entire plate broke down into fragments. Each fragment represents a different life, formed through this organic and unpredictable dissolution. Just like in life, the process is random and uncontrollable. We can only accept change—we cannot direct it. This reflects my understanding of existence: life shapes us in unique and unexpected ways, beyond our control.

Primo series in different stages

Reach Out To Acherologist

My interest in archaeology led me to look for ways to collaborate with archaeologists. I found several lectures online and attended some in person, where I spoke with students to learn more about archaeology and history. When I shared my passion for prehistory and the Stone Age, they recommended I speak with Professor Ulrike Sommer.

After one of her lectures, I approached Professor Sommer and told her about my interests, especially my desire to connect archaeology with art. She offered me some ideas and useful websites. I explained that I wanted to visit a prehistoric site for inspiration, and she suggested I go to Avebury.

Lecture at UCL institute of archaeology

During the Easter break, I visited Avebury. Avebury henge and stone circles are one of the greatest marvels of prehistoric Britain. Built and much altered during the Neolithic period, roughly between 2850 BC and 2200 BC, the henge survives as a huge circular bank and ditch, encircling an area that includes part of Avebury village. Within the henge is the largest stone circle in Britain - originally of about 100 stones - which in turn encloses two smaller stone circles. At there I felt so impressed and curious how they shape and moving these huge stones at that time, and I felt so small and can’t stop imagining the meaning or the purpose they made these circle. The shape of each stone really made me interested, they are so different, some of the stone looks like made of a piece of soft clay and the surface is full of holes and mold, really rough and strange, I took lots of photographs. Since then, I’ve been experimenting with etching and embossing and carborundum to create a new image inspired by what I saw. I want to emboss the stone elements to emphasize their texture and form—treating them almost as sculptural objects—while drawing the sky as a dark, mysterious backdrop.

For the sky, I took inspiration from one of my favorite artists, Edvard Munch. I’m drawn to the way he uses dark shadows to evoke sadness and sorrow, creating an uncanny atmosphere. I believe this sense of mystery is a powerful way to express the unknown.

Through this work, I aim to explore the contrast between what we think we understand and what remains beyond our grasp. The embossed stone is bold and prominent, symbolizing humanity’s belief that we understand the world—often in a self-centered way. In contrast, the sky represents the vast, unknowable universe: dark, deep, and waiting to be discovered.

Stone circles in Avebury

Mix soil with glue

Etching steel plate

Carborundum test

A part of the stone

Shark teeth in the soil

Etching test

Folklore about Hagstone

I don’t know the stone with a natural hole in it called Hagstone, after I talked to Professor Ulrike Sommer, she told me the folklore behind it, which is really fascinating to me. Actually there are many stories about Hagstone. Which I find out really fascinating.

According to Ancient Roman natural philosopher Pliny’s Natural History, book XXIX, adder stone was held in high esteem amongst the Druids. Pliny described rituals the druids allegedly conducted to acquire the stone, and the magical properties they ascribed to it. He wrote:

There is a sort of egg in great repute among the Gauls, of which the Greek writers have made no mention. A vast number of serpents are twisted together in summer, and coiled up in an artificial knot by their saliva and slime; and this is called "the serpent's egg". The druids say that it is tossed in the air with hissings and must be caught in a cloak before it touches the earth. The person who thus intercepts it, flies on horseback; for the serpents will pursue him until prevented by intervening water. This egg, though bound in gold will swim against the stream. And the magi are cunning to conceal their frauds, they give out that this egg must be obtained at a certain age of the moon. I have seen that egg as large and as round as a common sized apple, in a chequered cartilaginous cover, and worn by the Druids. It is wonderfully extolled for gaining lawsuits, and access to kings. It is a badge which is worn with such ostentation, that I knew a Roman knight, a Vocontian, who was slain by the stupid emperor Claudius, merely because he wore it in his breast when a lawsuit was pending.

In Russian folklore, adder stones were believed to be the abodes of spirits called Kurinyi Bog ("The Chicken God"). Kurinyi Bog were the guardians of chickens, and their stones were placed into farmyards to counteract the possible evil effects of the Kikimora (The wives of the Domovoi, the house spirits.) Kikimora, who also guarded and took care of chickens, could often unleash misery upon hens they did not like by plucking out their feathers.

In the seaside town Hastings there is a local legend that the town is under an enchantment known as Crowley's Curse, said to have been conjured by Aleister Crowley who lived in Hastings at the end of his life. The curse compels anyone who has lived in Hastings to always return, no matter how far away they move, or for how long. The curse can only be broken by taking a stone with a hole running through it from Hastings beach.

The hagstone i found when i mud larking around Thames

Henry Moore Studio & Gardens

Henry Moore created many prints based on the elephant skull, as well as a series on Stonehenge. I was especially drawn to the way he used color and line to explore these forms from various angles, offering the viewer a visual journey through prehistoric sites and natural structures. His approach inspired me to begin my own series on the Avebury stone circle. However, I’ve chosen a different direction—my work hints at the depth and mystery of the universe. Rather than simply documenting the stones, I aim to evoke a sense of the unknown and the vastness beyond human understanding.

Later, I visited Henry Moore’s studio and gardens, which further inspired me. That experience encouraged me to start collecting more natural forms and objects as part of my own creative process. I already did some casting and wax sculpture in the unit 1, and also casted the hagstone which I found when I mud larking, See more process how to casting click here.

Casting of hagstone

Photos from Henry Moore’s studio and gardens

Process of casting hagstone

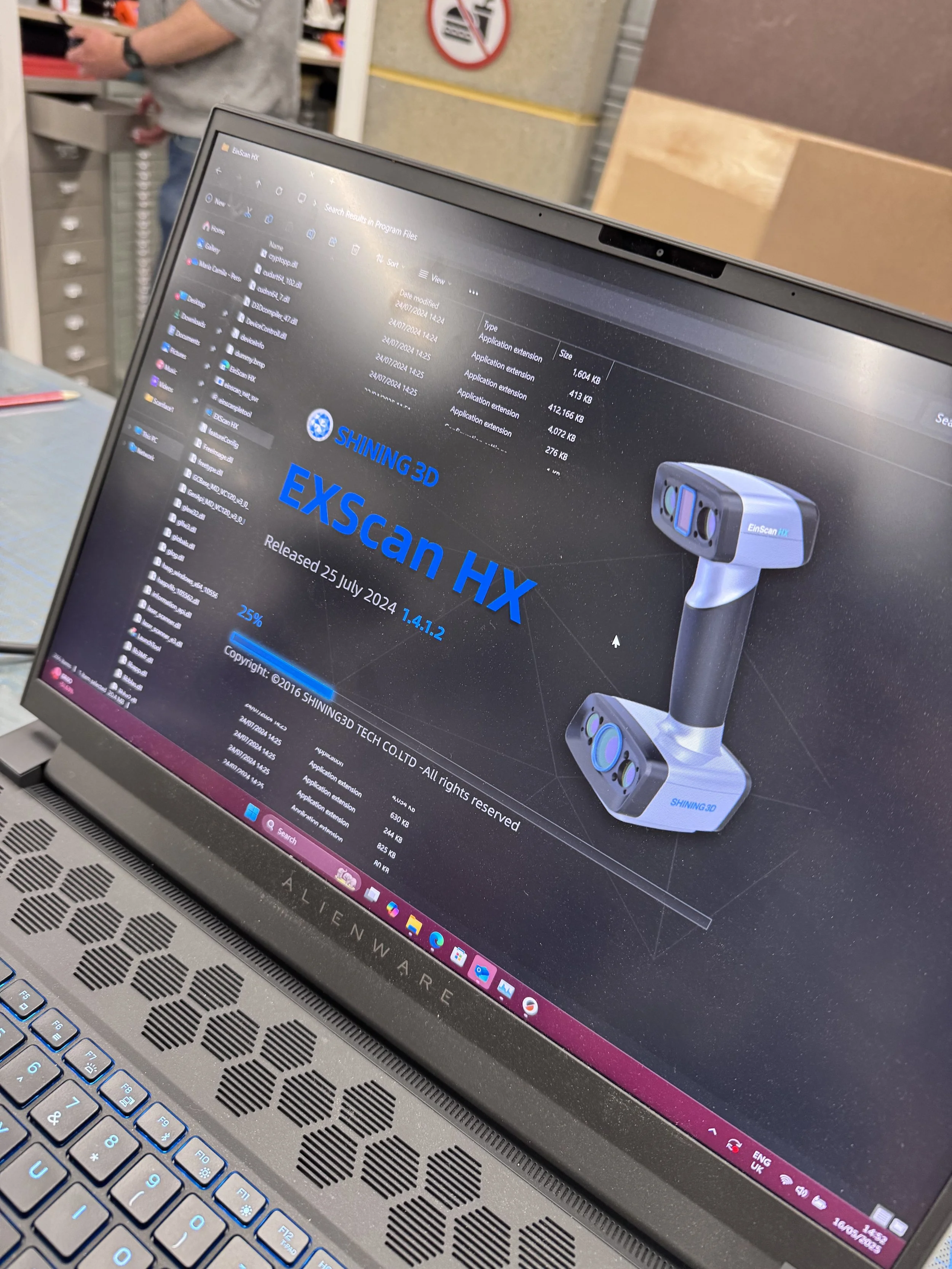

3D scanning and animation test out

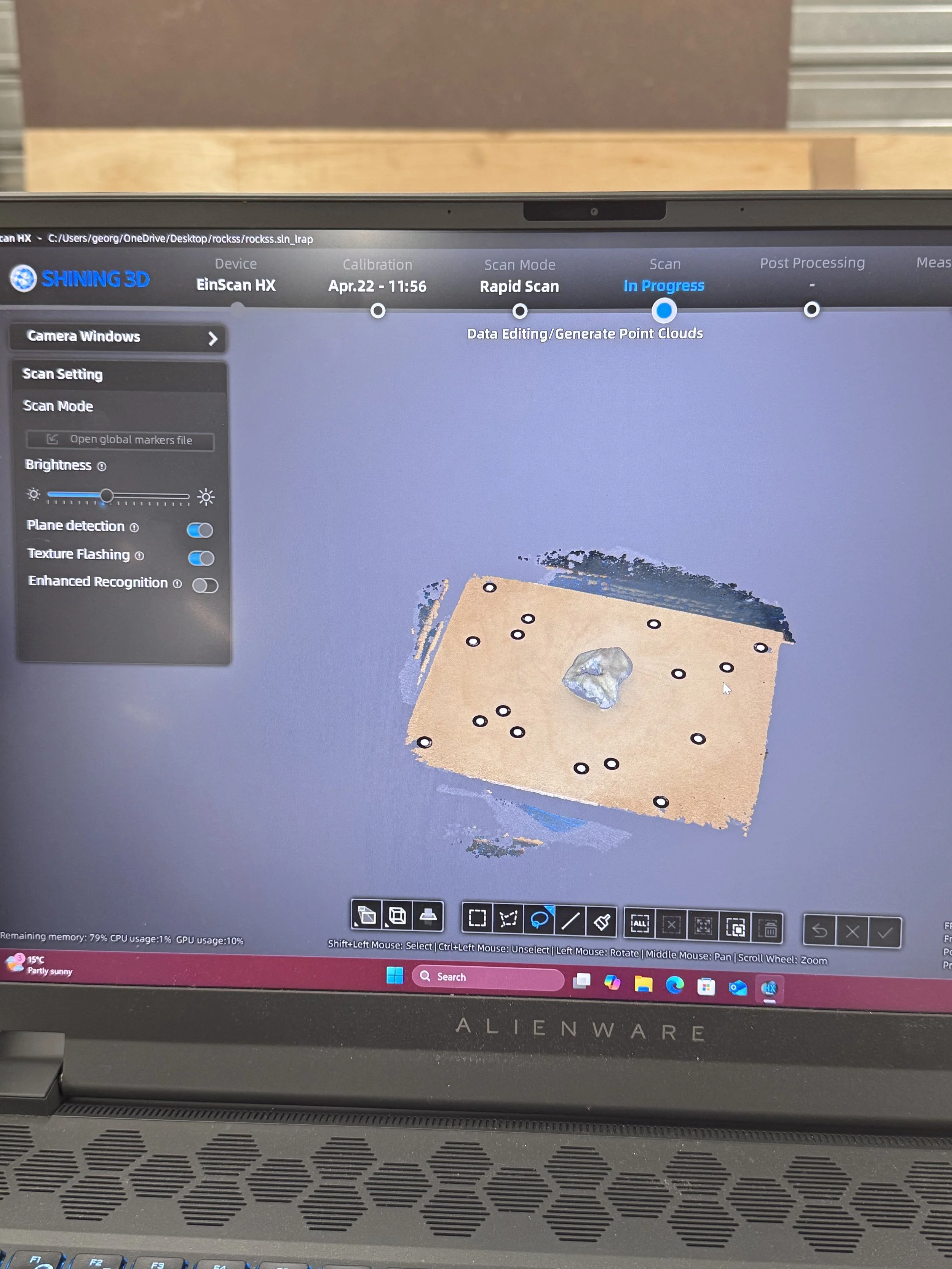

After my solo exhibition, Jo gave me some suggestion, which she mentioned there are something potential about the video, and i also talked to her about the degree show, i want to some sculpture as an extender for my prints, she suggested me to try 3D scanning, so i come to the workshop and talk to the technician they helped me to do the scanning, which i found really interesting, but i found point cloud is more interesting than the the full scanning because my prints also as a fragments, not a whole, which represent the evolving of life and the part of history, just like when you found something in archaeological excavation, you always find pieces not the whole object, so i will test more with 3D scanning.

Connect 3D scanner to the computer

Scanning the object

Scanning the object

Hagstone animation

Combine two side together

Reference Artists

Rachel Witeread

Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures and drawings transform everyday objects, settings, and surfaces into ghostly, hauntingly familiar replicas. Through the process of casting, she liberates her subjects—ranging from beds and tables to water towers and entire houses—from their functional roles, giving them a new, lasting presence infused with memory and absence.

I’m particularly drawn to the way she pays close attention to ordinary objects—an interest we share, especially in the context of casting. I remember seeing her 12 Objects Etching Box at Paupers Press; the subtle beauty of those prints left a strong impression on me. I also admire her restrained use of color in her prints and the minimalist approach she brings to her exhibition presentations. Her show Internal Objects especially resonated with me for its quiet power and refined aesthetic.

12 Objects, Etchings Portfolio of 12

Internal Objects

2. Nika Neelova

Often working with reclaimed architectural materials, Nika Neelova explores how material and architecture shape our perception of time and place. Rather than using straightforward methods of fabrication, her practice is focused on uncovering and revealing the latent histories embedded within objects—retrieving traces of human presence through inanimate forms. Her work imagines alternative narratives of the past through what she calls ‘reverse archaeology,’ examining architectural remnants and found objects, then transforming them beyond their original function. In doing so, her sculptures retain a sense of the human body and touch as residual memory.

Neelova’s practice draws connections across time and disciplines. Her sculptures feel like fragments of larger cycles, momentarily frozen in their current forms. She places strong emphasis on material transformation—on translating objects into new mediums, altering their internal structures, and freeing them from their intended meanings.

I discovered her work on Instagram last year and was immediately drawn to it. I admire how she uses handmade processes to explore historical themes, and how her deep knowledge of archaeology informs her artistic thinking. Her approach is incredibly inspiring, both conceptually and visually. One of the first works that stood out to me was Glyphs, a signature piece she created during a residency, in which she transformed old architectural handles into sculptural forms that suggested entirely new stories. I also found her recent solo exhibition fascinating—especially her new works inspired by shark teeth, which she described in a video as continually regenerating, much like a living system or tree of life. This metaphor was beautifully rendered in sculptures that resembled branches.

Her collaboration with archaeologists is particularly meaningful to me, as it aligns with the direction I hope to take in my own practice—bridging art and historical inquiry through material and form.

Beghost, 2024

Fossilised shark teeth, clay, epoxy, rope

Beghost, exhibition

Glyphs by Nika Neelova

3. Michal Rovner

I saw Michal Rovner’s work in Pace gallery the other day, her exhibition Michal Rovner Pragim. I found it’s really intersting, i like her film so beautiful and technological, after that, i find out more about herself and turns out i love all of her work, and we have some same interests which inspired me to do more film and use more technology. Her work shifts between the poetic and the political to explore questions of nature, identity, dislocation, and the fragility of human existence.

Michal Rovner's layered and intentionally ambiguous work touches on the processes of historical documentation, archaeology, science, and choreography to activate states of probing.

Her installations are constructed out of materials ranging from symbolic stones to a video-photography-printmaking hybrid of her own invention. Rovner places actors in her short film pieces, however, they are shrouded in black and often difficult to differentiate against the backdrop of the desert, making them emblematic and anonymous figures, as in her 2003 short film More. At the other end of the spectrum are her works Makom / and // (2007-2008), four-walled installations built out of cubic stones that were once part of Israeli and Palestinian homes in which Rovner used ancient stone masonry techniques to construct the structures.

Makom, 2008, France

Michal Rovner Paagim, Pace gallery, 2025

In conclusion, throughout this unit I explored a variety of techniques and made meaningful progress in both my artistic practice and theoretical understanding. I experimented with metal casting, 3D scanning, and embossing, as well as carborundum printing and plaster sculpture. While some results—like the carborundum and plaster works—are still in progress and not yet fully resolved, the process has been valuable for my development.

Looking ahead to Unit 3, I plan to deepen my theoretical research and actively seek connections with archaeologists and scientists. I hope to engage in interdisciplinary collaborations or uncover new insights that can enrich my art practice.

I’m truly grateful to my classmates, friends, and tutors for their ongoing support and encouragement throughout my studies.

Bibliography

Books:

Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (1819) Schopenhauer

Romance in the age of Uncertainty (2003) Damien Hirst

The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, (Collected Works of C. G. Jung), Routledge; 2nd edition (6 Jun.1991)

Being and Time, Martin Heidegger, Harper Perennial, 2018

Object- Oriented Ontology, Graham Harman, Penguin Books,2018-03-01

Parker, C. and Schlieker, A. (2022) Cornelia Parker. London, England: Tate Publishing.

Stewart, S. (1993) On longing: narratives of the miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir, the collection. Durham, N.C., London: Duke University Press

Bennet, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bogost, I. (2012) Alien Phenomenology or What it’s Like to be a Thing (Posthumanities). Minnesota: Minnesota University Press.

Groys, B. (2017) Curating in the Post-Internet Age, e-flux journal #94 October

Hawkins, H and Olsen, D, eds. (2003) The Phantom Museum and Henry Wellcome’s Collection of Medical Curiosities, London: Profile Books

Leslie, E. (2005) Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion Books.

Lilley, C. (2015) Materiality. London: MIT Press/Whitechapel Gallery.

Lowenhaupt Tsing, Anna (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton: Princeton University Press

The poetry of forms Arp, Eric Robertson Frances Guy, Kröller-Müller MuseumMuseum

Henry Moore Prints and Portfolios, David Mitchinson, (2010) Patrick Gramer, Switzerland

Figuring it out, Lord Colin (2003) Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Tao Te Ching, (1993) Hackett Publishing Co, Inc

Website:

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Reel.

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/94/219462/curating-in-the-post-internet-age/

https://susanaldworth.com/exhibitions/modern-alchemy-towards-a-more-sustainable-chemistry/

https://katherine-jones.co.uk/about/

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jean-arp-667

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/taoism/

https://www.pacegallery.com/exhibitions/michal-rovner-pragim-london/

Videos:

https://youtu.be/LrRc3sT2vXo?si=MKKHhKLsIaMM5iKO

https://youtu.be/dkqJmMECZCs?si=EpQGqPtsAXDzyxcu

https://youtu.be/CZN3fN1kWiw?si=3WWcDW2LhDizvvLu

https://youtu.be/pmv3J55bdZc?si=_zIh_xAnPdHIJTup