Talking Painting Artist’s Talk: Simon Callery

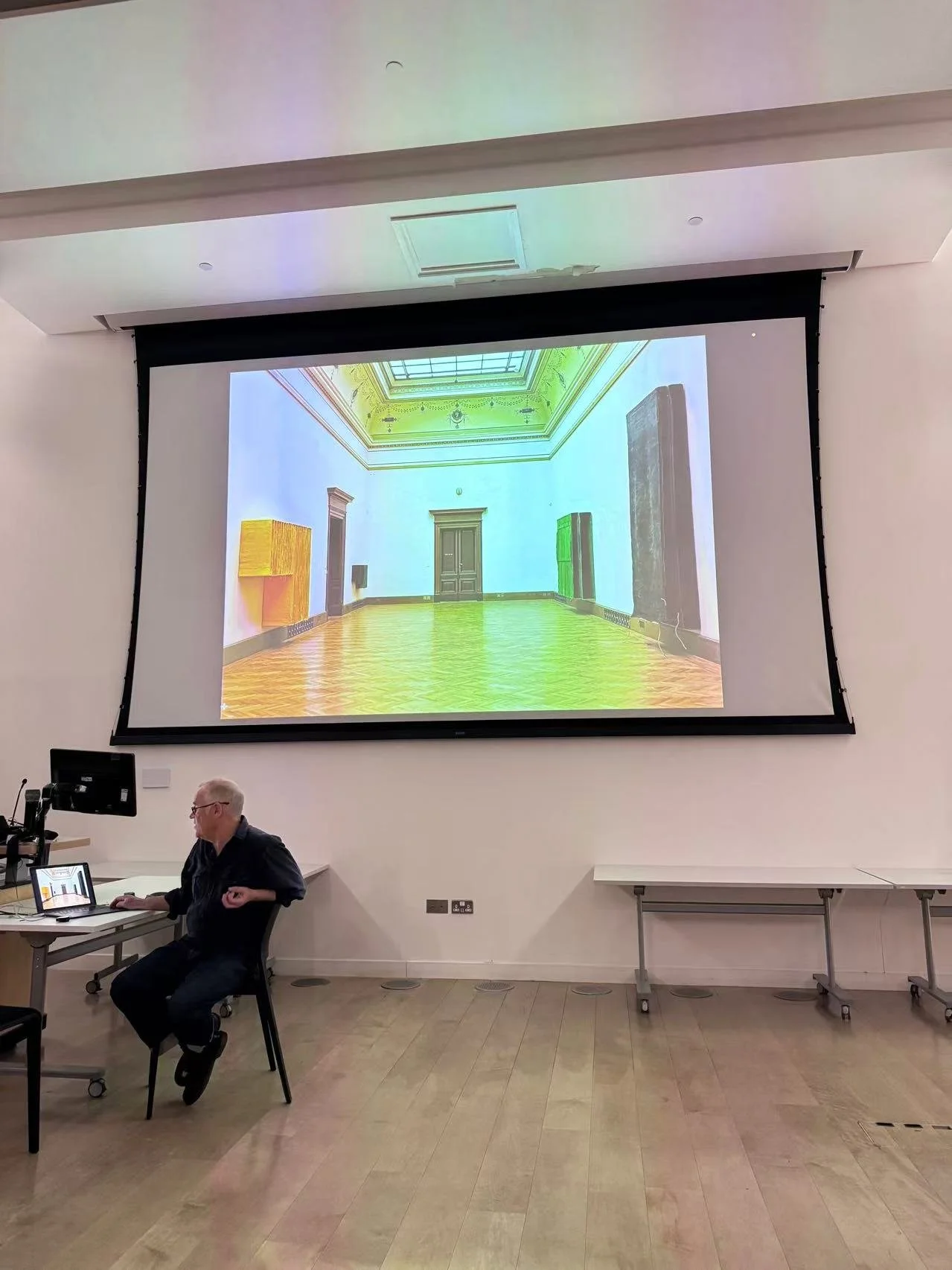

Simon Callery gave us a talk, which I found very inspiring and engaging. I was particularly interested because, like him, I am fascinated by archaeology. His practice pushes the boundaries of contemporary painting. He has collaborated on several long-term projects with archaeologists, which led him to develop multi-sensory, physical paintings that challenge the dominance of the image in art and everyday life.

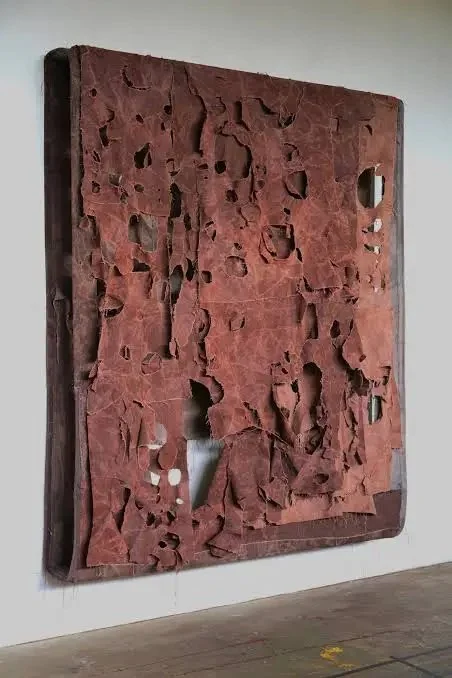

He showed us his unconventional oil paintings, where he uses canvas not just as a surface but as a material that evokes the ground itself. Much of his work is created directly in archaeological sites, where he cuts multiple holes into the canvas, creating layered installations that resemble excavated earth. I found this approach deeply interesting and inspiring.

After the talk, I had the chance to speak with him. I was surprised to learn that his first collaboration with archaeologists began through an invitation — it made me realize that opportunities often come when you focus on doing your own work authentically. He also shared valuable advice: start reaching out to small galleries or organizations that interest you, and consider proposing your own art residency — or even creating one independently. I found his insights incredibly useful and motivating.

Simon Callery’s artist talk

Simon Callery’s art work

Simon Callery’s art work

Visit Chelsea College of Arts Archive

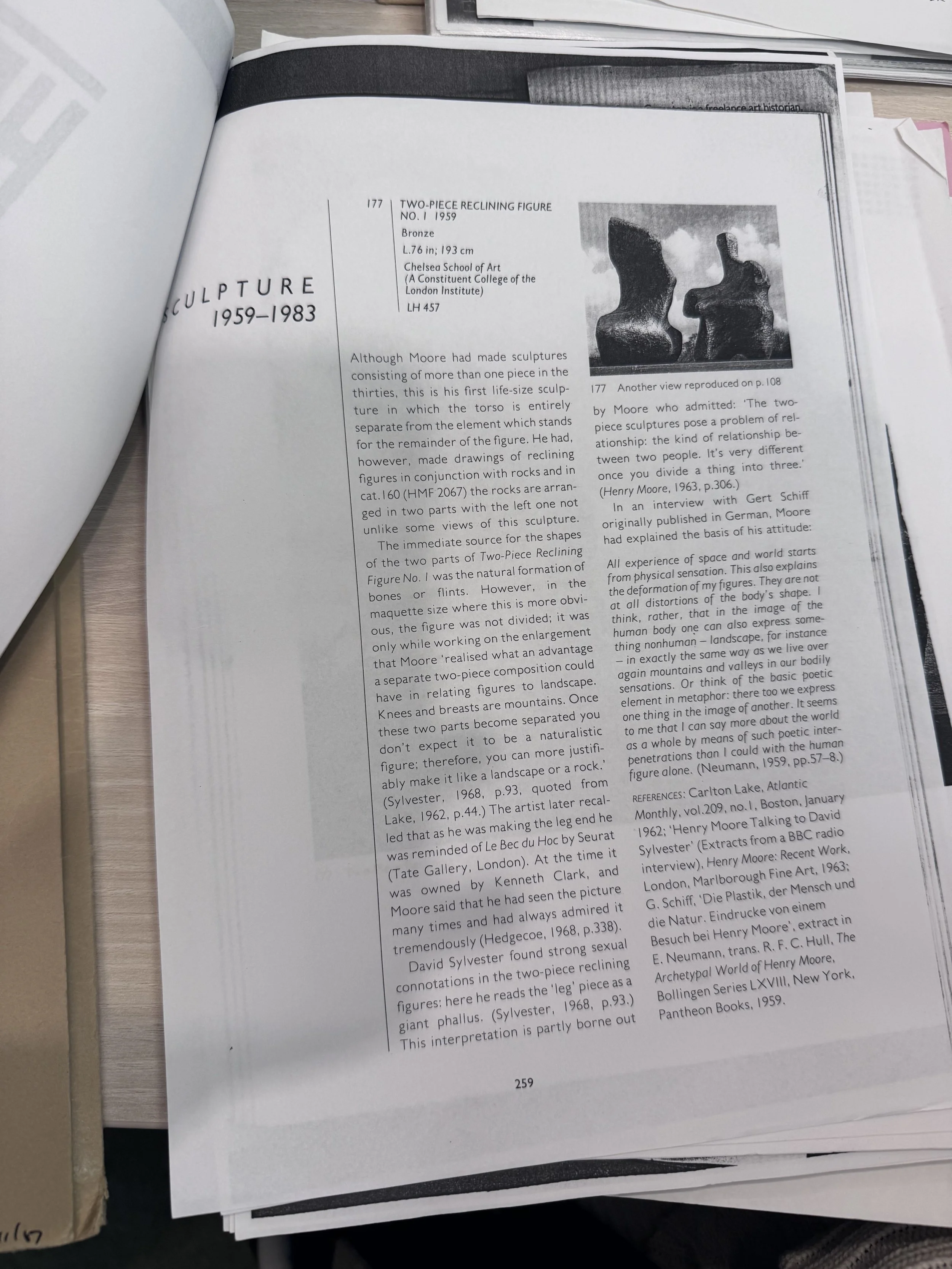

I have been deeply interested in Henry Moore’s work for some time, so I was excited to discover that the Chelsea College of Arts holds an archive related to his practice. I booked an appointment to visit and explore the collection in person. The archive focuses on Moore’s bronze sculpture Two-Piece Reclining Figure No. 1 (1959), which was purchased by Chelsea School of Art in 1963. When the new purpose-built school opened on Manresa Road, it was proposed that a major artwork should be acquired. The governors decided to purchase a sculpture by Moore, who had served as Head of Sculpture at Chelsea School of Art from 1932 to 1939, as recorded in the meeting minutes from 1963–1964.

This sculpture marks a significant moment in Moore’s artistic development—it was the first time he divided the reclining figure into two parts. As Moore explained:

“I did the first one in pieces almost without intending to. But after I had done it, then the second one became a conscious idea. I realized what an advantage a separated two-piece composition could have in relating figures to landscape. Knees and breasts are mountains. Once these two parts become separated, you don’t expect a naturalistic figure; therefore you can justifiably make it like a landscape or rock.”

(Wilkinson, A., 2002, pp. 287–288)

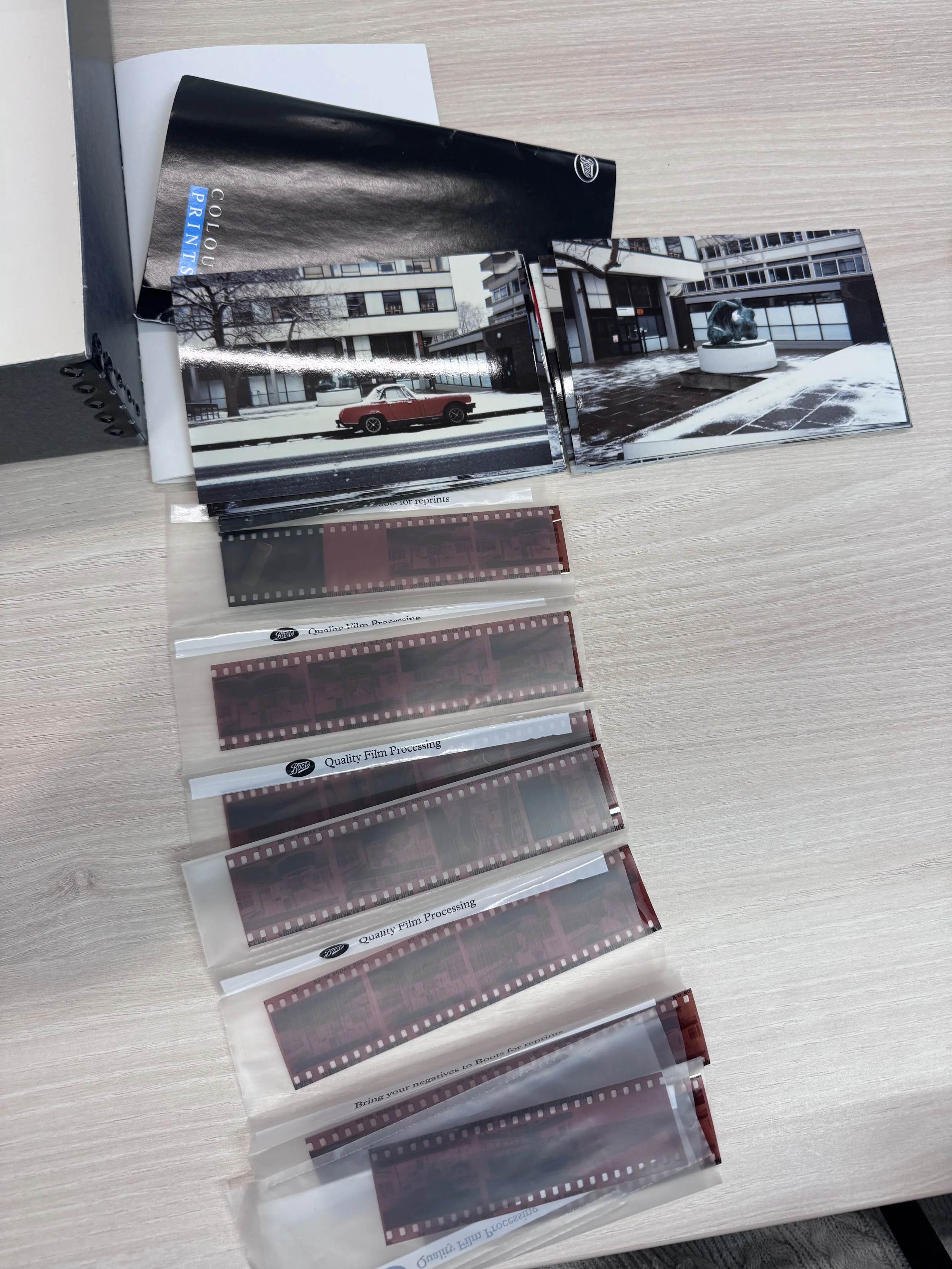

The documentation in this collection includes architectural plans by the London County Council for the sculpture’s plinth and placement within the school grounds, as well as black-and-white photographs from its installation on 25 March 1964. There is also correspondence between Moore and various institutions regarding the installation and later movements of the sculpture.

Other materials trace the sculpture’s loan history to major exhibitions, including the Tate Gallery retrospective (1968), the Royal Academy (1988), and Jeu de Paume (1996), along with colour photographs documenting its relocations. A highlight of the archive is a pencil sketch of the sculpture by Moore himself. Seeing these original photographs, letters, and drawings was fascinating and allowed me to gain a deeper understanding of Moore’s sculptural process and artistic vision.

Branch of Moore’s work

Branch of Moore’s work

Archive box

Sculpture map

Photos of sculpture

Detail’s about sculpture

A Trip to Kettle’s Yard

During the summer break, I visited Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, which was a profoundly meaningful experience for me. It was the first time I encountered the works of Ben Nicholson and Italo Valenti, and I was immediately drawn to both artists. I was especially captivated by the simplicity of Nicholson’s lines and his cut-out forms, which convey a quiet sense of balance and structure. At the same time, I was deeply impressed by Italo Valenti’s torn paper compositions, discovering how something as fragile and spontaneous as a tear could become such a beautiful and expressive element in art. After returning from the visit, I began studying their practices more closely and created a series of artworks inspired by their approaches to form and abstraction.

Living room

Ben Nicholson’s art work

Italo Valenti’s art work

Ben Nicholson’s art work

Italo Valenti’s art work

Table and Ben Nicholson’s art work