Key Words :

Existence, New materiality, Transformation

Theme: The Vitality of Matter and the Question of Existence

Through my art practice, I seek to explore the question of human existence. I am particularly fascinated by the origins of life, prehistory, and the mysterious past of the universe — questions that continue to drive my creative process. The constant transformation and unpredictability of life deeply intrigue me, and I aim to express these ideas through my work. I draw inspiration from philosophy and use contemporary technologies as tools to deepen my understanding of life. My interests in archaeology and science also guide my practice, as I see them as modern methods for exploring the universe and our place within it.

Philosophy has always been at the core of my artistic thinking. I am strongly influenced by new materialism, existentialism, and Taoism. My obsession with shapes, formations, and materials reflects my attempt to understand the essence and vitality of life itself. Science and archaeology also play a vital role in my creative process. Whether observing microscopic structures or collecting objects along the shore, I see each trace as evidence of life and time. These discoveries help me create art that connects ancient questions with our contemporary world.

Philosophical and Theoretical Context

My work engages deeply with theories that question the boundaries between life and matter. Both Zhuangzi’s Qiwu Lun (“On the Equality of Things”) and Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter challenge human exceptionalism and offer ways to understand the agency of nonhuman entities. Zhuangzi dissolves the dualities of life and death, being and non-being, suggesting that all phenomena emerge and transform within the flow of the Dao — a boundless, self-generating force. Similarly, Bennett’s new materialist philosophy argues that so-called inanimate matter possesses vitality and agency, urging us to see materials not as passive objects but as active participants in shaping the world.

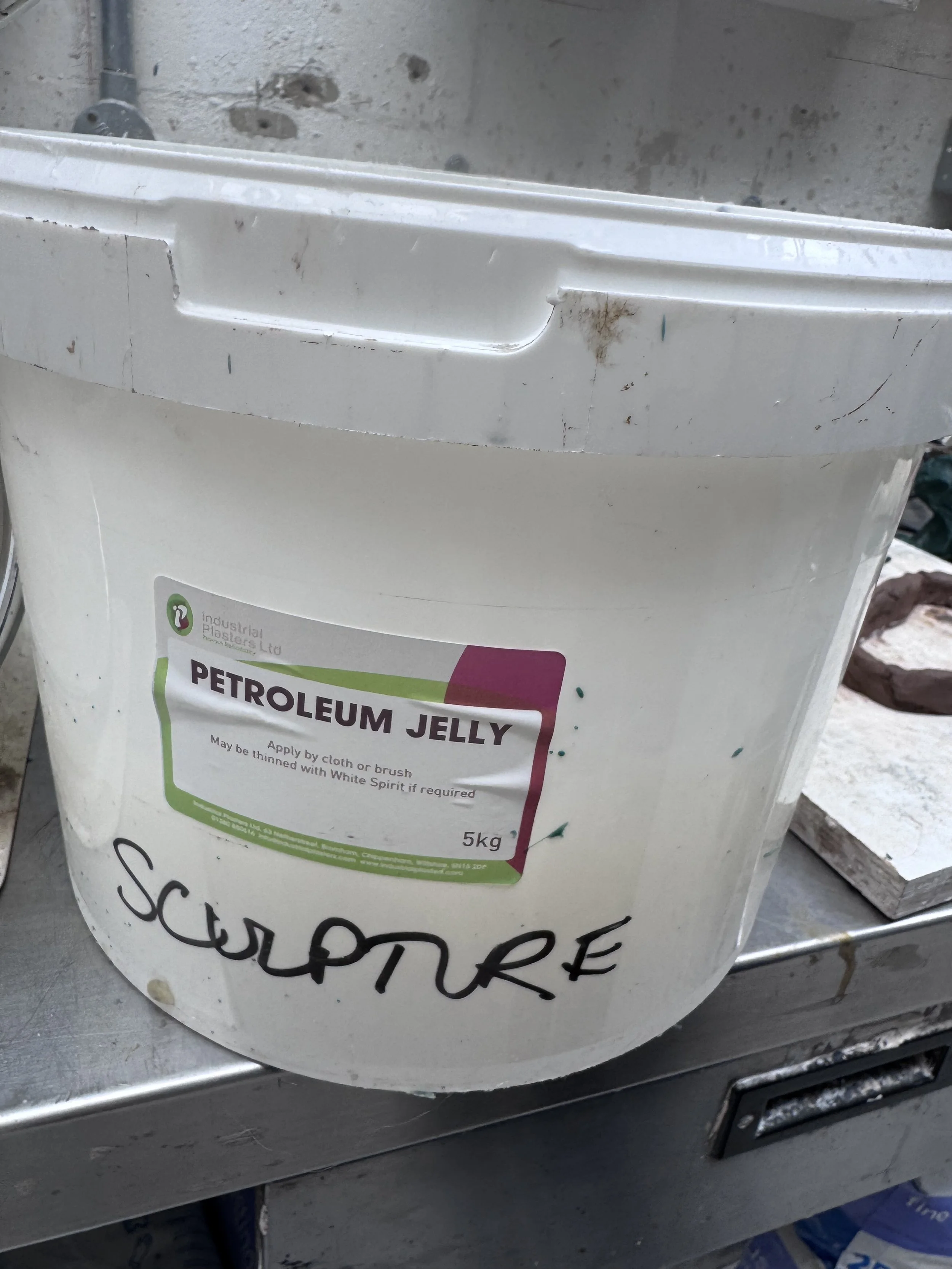

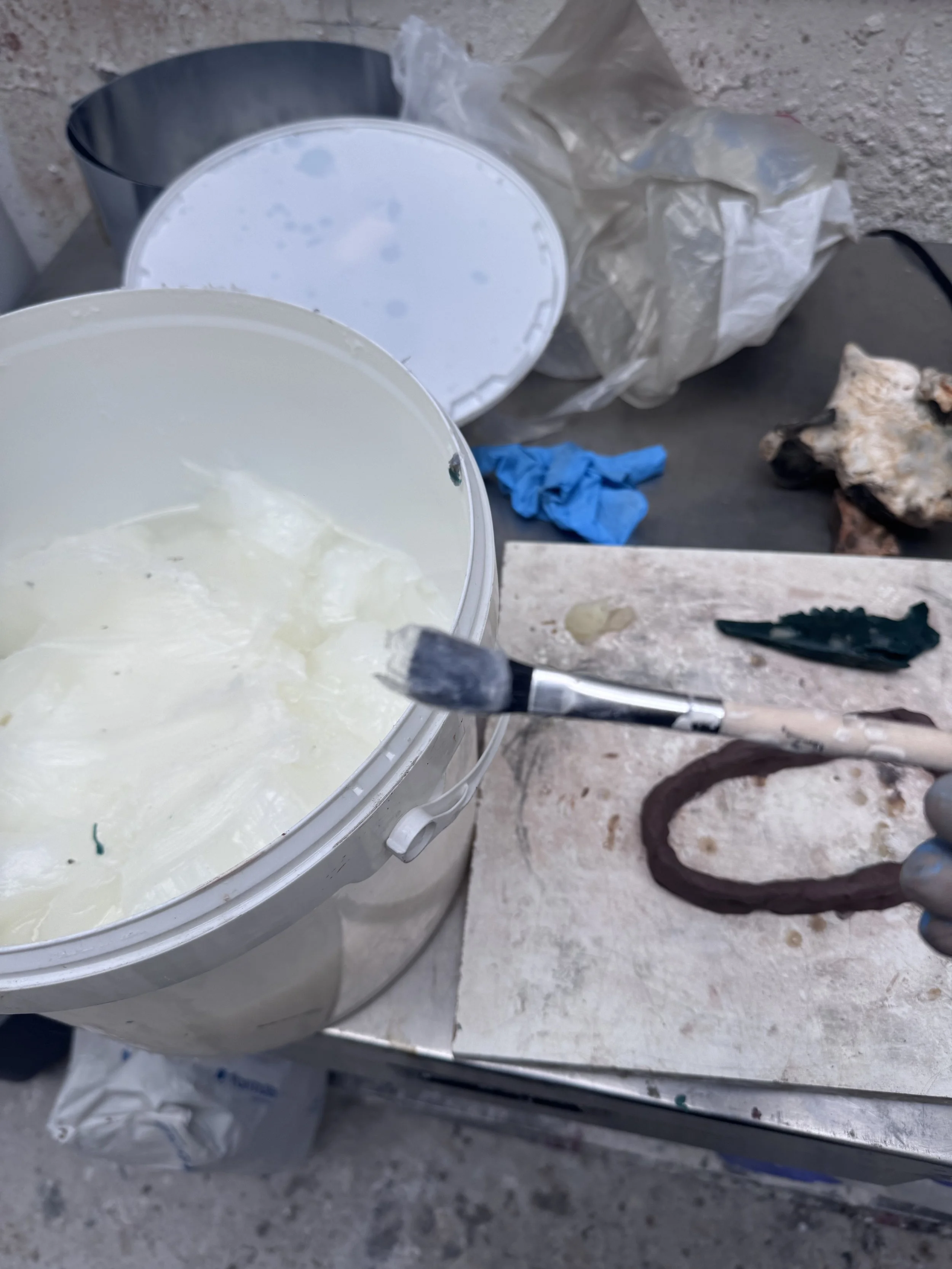

These ideas strongly resonate with my own experience in the studio. When working with substances such as wax, metal, and stone, I often find that materials possess their own rhythm and momentum — they resist, adapt, and transform in ways that go beyond my control. This challenges the anthropocentric idea of the artist as the sole author or controller of form. Instead, my creative process becomes a collaboration between human intention and material agency, echoing both Zhuangzi’s concept of wu wei (non-interference) and Bennett’s idea of thing-power — the capacity of matter to act on its own terms.

Vibrant Matter and Taoism

I first encountered Vibrant Matter through my professor, who suggested it after observing my fascination with transformation and organic processes. Reading the book profoundly changed how I perceive the relationship between humans and the material world. I had always intuitively felt that the natural environment and human beings are part of one unified system, but Bennett’s writing gave me a philosophical language to articulate that intuition. She proposes that all entities — human, animal, mineral, mechanical — participate in a shared field of vitality. This aligns with Taoist ideas that the universe is an interrelated whole, where all things continuously transform rather than remain fixed.

1. Thing-Power and the Materiality of Chance

In Chapter 1, Bennett discusses Lucretius’s notion of “bodies falling in a void” — atoms that are constantly in motion, colliding and swerving, generating new formations through spontaneous encounters. Without such deviation, the world would remain static; nothing new could arise. This “materialism of the encounter,” later developed by Althusser, describes a universe animated by chance, where emergence itself is the creative principle.

I find this idea deeply poetic. It reveals a world that is not governed by linear causality or divine order, but by a dynamic interplay of random forces and material tendencies. In my work, I embrace this element of unpredictability. For instance, when wax melts or metal oxidises, the final form cannot be fully anticipated — each outcome is a record of material contingency. The concept of thing-power allows me to see these processes not as flaws or accidents, but as manifestations of vitality. Like Lucretius’s atoms, my materials are in constant motion, falling, colliding, and transforming.

2. The Vitality of Matter

Bennett draws upon Hans Driesch’s theory that even inorganic matter may display formlike tendencies — that order and life-like qualities can emerge without biological intent. This radical notion challenges the long-standing assumption that matter is inert until acted upon by human will. It also resonates with Zhuangzi’s worldview, where rocks, water, and clouds are part of the same living continuum.

In my practice, I translate this concept into visual form. The Transience series, for example, consists of wax sculptures created by interrupting the cooling process midway. By submerging the semi-molten wax into cold water, I allow the shapes to solidify unpredictably, capturing a moment of transformation. Each piece appears alive — still in the process of becoming. I realised that vitality does not belong only to biological organisms but also to the behaviour of materials themselves. The vitality of matter, for me, becomes a metaphor for existence: fragile, shifting, and never complete.

3. Humans as Material Assemblages: Shi and Taoist Resonances

One of the most striking moments in Bennett’s book is her discussion of the Chinese concept Shi — a term describing the potential energy or tendency that arises from the arrangement of things. Shi captures the idea that power is not always intentional; it can emerge from relational dynamics and the inherent disposition of matter.

This concept connects directly with Zhuangzi’s philosophy, where the Dao operates through effortless transformation, and every entity possesses its own ziran (self-so-ness). Both traditions decentralise human agency and highlight the active role of nonhuman forces.

In my own creative process, I experience this Shi when materials start to guide me rather than the other way around. When I cast bronze or let wax melt, I am no longer in full control — the work unfolds through the material’s own potential. This surrender to Shi aligns with Zhuangzi’s teaching of non-interference: to follow the flow rather than impose will. The resulting forms embody both philosophical and physical balance, existing between order and chaos.

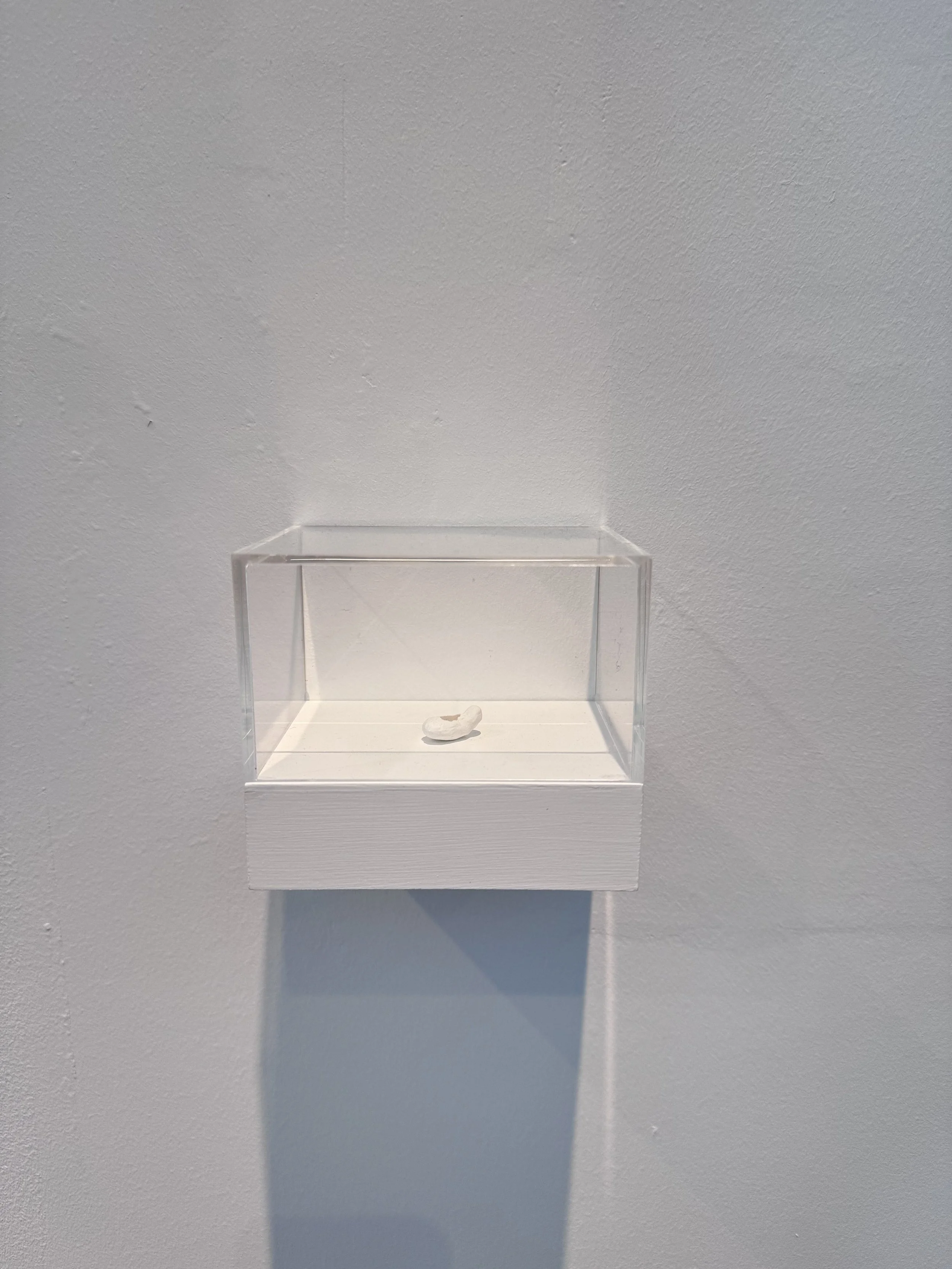

From Theory to Practice: Experiments with Material Agency

After reading Vibrant Matter, I became increasingly interested in how to reveal vitality within inanimate matter. I began with a small hagstone I found while mudlarking along the Thames — a naturally eroded stone with a hole through its centre. Its form fascinated me because it embodied geological time, slow erosion, and accidental beauty. I cast the hagstone into six different materials: Mixed plaster with aluminium power, bronze, plaster, pewter, aluminium, and Mixed plaster with soil. Each material carried its own history and behaviour, producing subtle differences in texture and form.

This process led to a series of discoveries. The same shape behaved differently in each substance, revealing unique forms of resistance, fragility, and transformation. I realised that replication itself could become a method of philosophical inquiry — a way to explore the changing identities of matter through its own responses to external forces.

Later, when I revisited my earlier wax sculptures from the Life Series, I noticed that some had partially melted under sunlight. Their deformation was strangely beautiful; they seemed to be alive, shifting into new forms. This accidental event inspired the Transience series. By opening the silicone mould before the wax fully cooled and submerging it in cold water, I allowed the material to “decide” its final shape. The process became an experiment in non-control, a collaboration with matter’s inherent tendency to flow and solidify.

1.Pour the melted wax into the silicone mould.

5. Take out the wax sculpture when it is fully formed.

2.Put the silicone mould into a bucket of cold water.

3. Wait a few minutes then take out the wax.

6. Cut the extra part of the sculpture.

4. Failed work because I didn’t wait enough time.

7. Polish each one of the sculptures.

Theoretical Dialogue: Zhuangzi and Bennett

The more I engaged with Bennett’s writing, the more I recognised echoes of Zhuangzi’s Qiwu Lun. Both thinkers challenge hierarchical dualisms — subject/object, life/death, human/nature — and both propose that reality is a field of continuous transformation. However, their motivations differ. Zhuangzi’s philosophy aims for spiritual liberation, freeing the mind from rigid distinctions to achieve harmony with the Dao. Bennett’s approach, by contrast, is political and ecological; she redefines agency to address environmental crises and ethical relations with nonhuman entities.

In my work, I try to bridge these two dimensions — the metaphysical and the ecological. The act of casting, melting, and corroding materials becomes both a spiritual meditation and a political statement. By revealing the vitality of matter, I invite viewers to reconsider their relationship with the material world, not as masters but as participants in a shared continuum of existence. The process of working with materials becomes a form of listening — to their resistance, fragility, and energy — rather than imposing dominance.

Reflection on Related Exhibitions

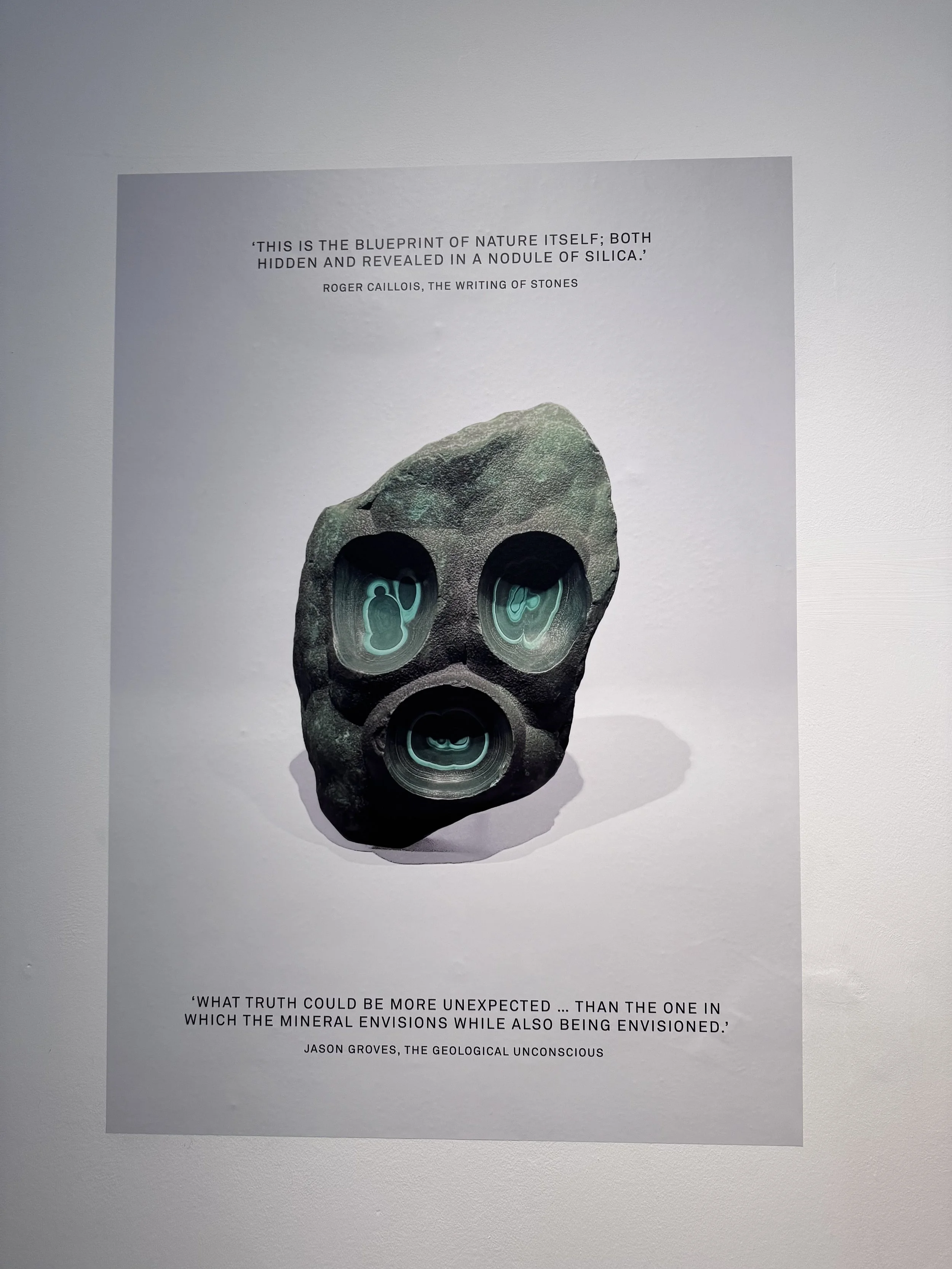

The Geological Unconscious

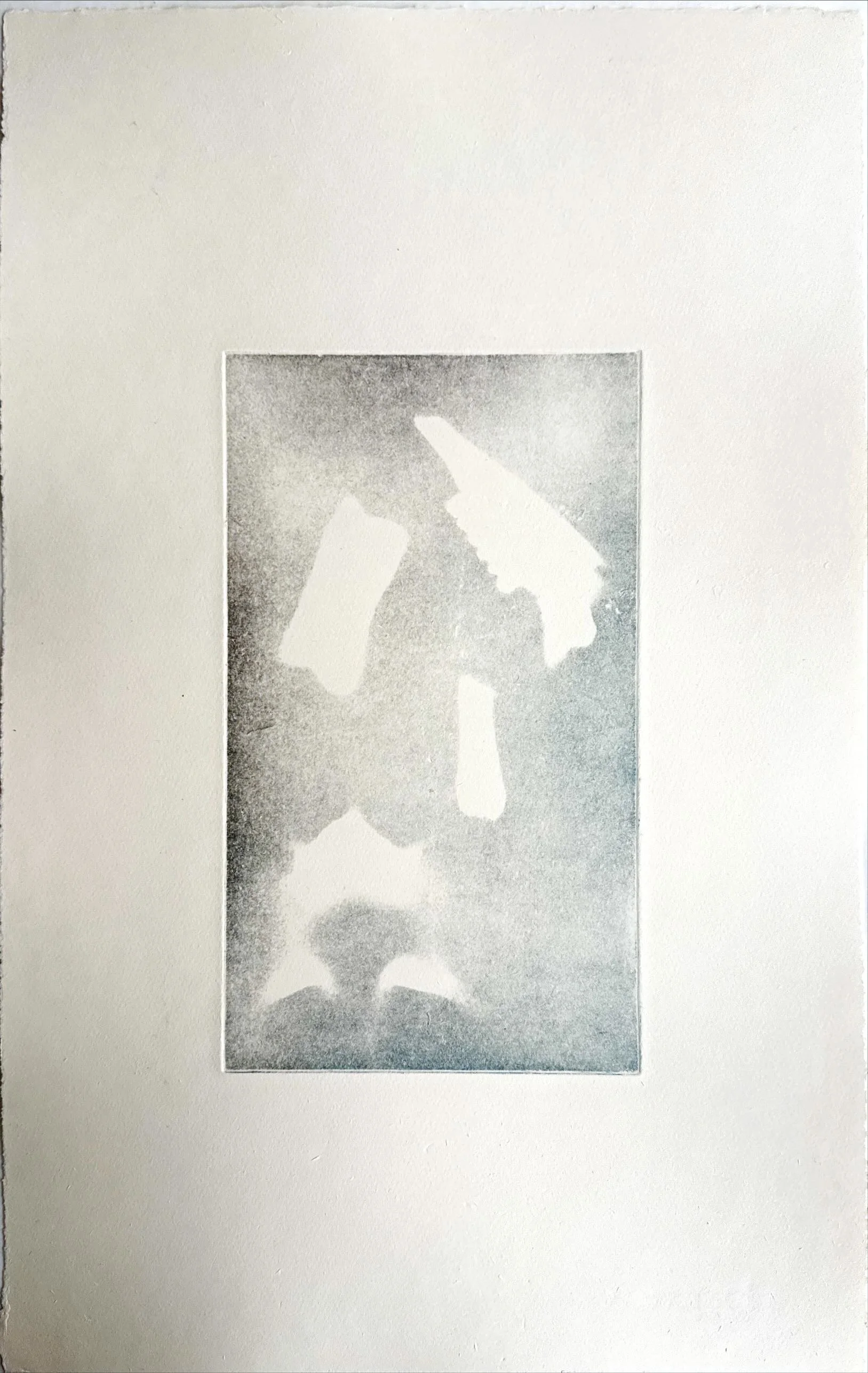

My visit to The Geological Unconscious exhibition significantly deepened my reflection on these ideas. The show explored themes of stone consciousness and human-mineral entanglements, destabilising assumptions about passive matter and a stable Earth. Artists like Julie F. Hill, Susan Eyre, Charlie Franklin, Rona Lee, and Deborah Tchoudjinoff presented works that reimagined geological time and mineral agency through sculpture, print, and video.

What struck me most was how these artists treated the geological as an active participant in human history. Works such as Hill’s asteroid-derived prints or Eyre’s video from the rock’s perspective embodied a form of material empathy — a shift of vision that aligns with both Bennett’s vibrant materialism and Zhuangzi’s idea of viewing the world “from the perspective of things.”

The exhibition also confronted the political consequences of extractivism, showing how human exploitation of minerals disrupts the planet’s equilibrium. I realised that my own practice, while rooted in philosophical contemplation, also engages with these ecological issues. The bronze I cast or the wax I melt are not neutral materials — they belong to broader networks of production, energy, and waste. Recognising this expanded the ethical dimension of my work: to be attentive to where materials come from and how they continue to act beyond the studio or gallery.

Poster at the exhibition

Art work by Julie Hill

Art work by Rona Lee

Art work by Julie Hill

Art work by Susan Eyre

Art work by Bodie Stanley

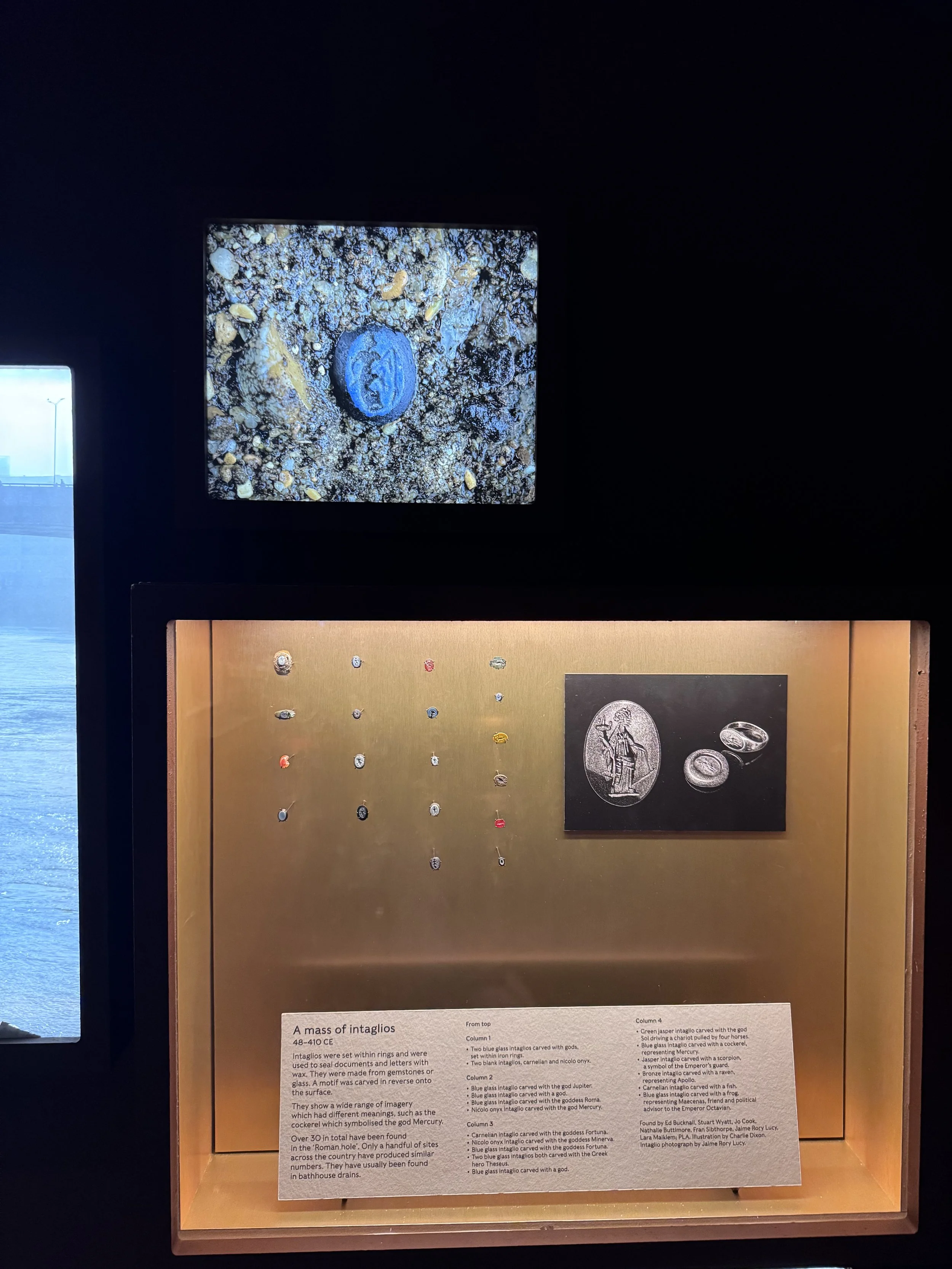

Secrets of The Thames: Mudlarking London’s Lost Treasures

The exhibition Secrets of the Thames: Mudlarking London’s Lost Treasures, held at the Museum of London Docklands, is the first major show dedicated to the practice of mudlarking and the archaeological discoveries along the River Thames. It presents over 350 objects found on the Thames foreshore — from medieval gold rings and Viking knives to 18th-century dentures and 16th-century wool caps. For me, this exhibition directly resonates with my own artistic practice, which began with mudlarking along the Thames. It revealed how these overlooked fragments — exposed and transformed by the tide — hold deep connections to the city’s history and to the personal lives of its inhabitants.

The exhibition inspired me to reach out to organisations working to protect the Thames and to preserve its historical and environmental heritage. I realised that these found objects are not just materials for art, but also traces of human presence and urban evolution. The way the exhibition transforms fragments into carriers of memory and meaning aligns strongly with my philosophy: that matter is not static but continuously shaped through time, environment, and human interaction. I now see my mudlarking practice as more than a search for material — it is an act of uncovering history and reconnecting with the living continuity of matter.

Stones and sword found in Thames

Found objects preserved in boxes

Overview of the exhibition

Stamp ring found while mud larking

You can see the view on screen by spining the wheel

Talking to a mud larker

Mudlarking objects I found which inspires my art practice

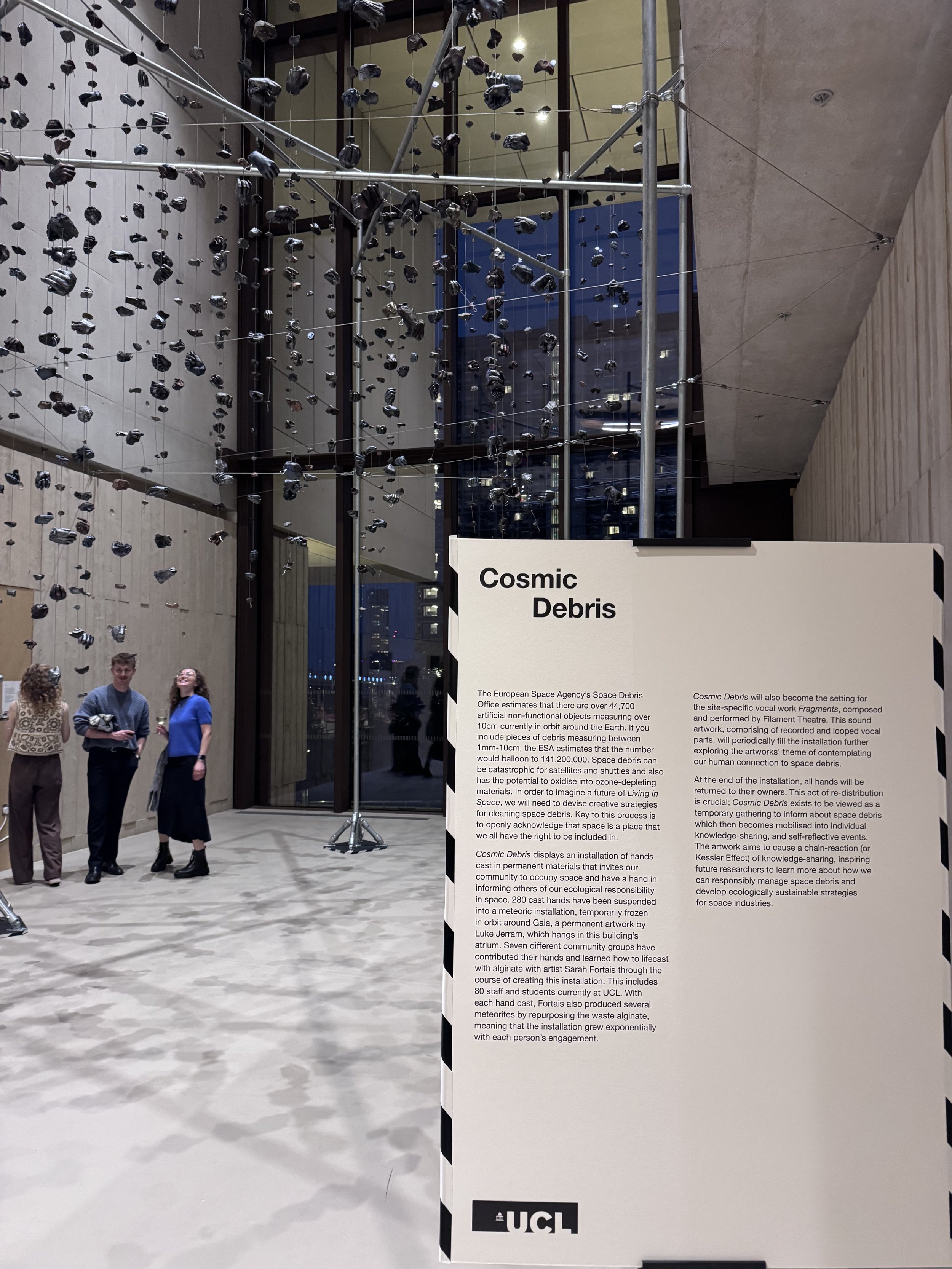

Space Tangle

Space Tangle, exhibited at UCL East campus, was curated by artist Sarah Fortais. The exhibition featured works such as Cosmic Debris — 280 cast hands suspended in orbit — and Cosmic Flock, a series of sheep-like sculptures made from recycled East London waste, each wearing a handmade “space suit.” Another work, Lunga 6, was developed during the UK’s first simulated space research mission. Through the lens of outer space, Fortais examined the relationship between humans, waste, ecology, and material transformation.

This exhibition made a strong impression on me. While my own work often explores the archaeological and microscopic — the fragments of life and time found on the Thames — Space Tangle opened up a new dimension, extending these ideas into a cosmic scale. It made me question how the concept of “fragment” could be reinterpreted as space debris, extraterrestrial matter, or future relics. The exhibition’s imaginative approach to materiality and waste encouraged me to think beyond earthly archaeology — to see my practice as part of a broader continuum that connects the origins of life, material decay, and the infinite processes of the universe. Inspired me to dig deep into the science aspect in my art work and gives me the idea making my artist book more scientific. So I decide use some images I observing under the microscope and have a magnifier glass inside of my artist book.

Art work

Art work

Sensory Table

Art work

Art work Cosmic Debris

Art work Lunga Ball 002 Vantity Sheep

Reflection on Degree Show

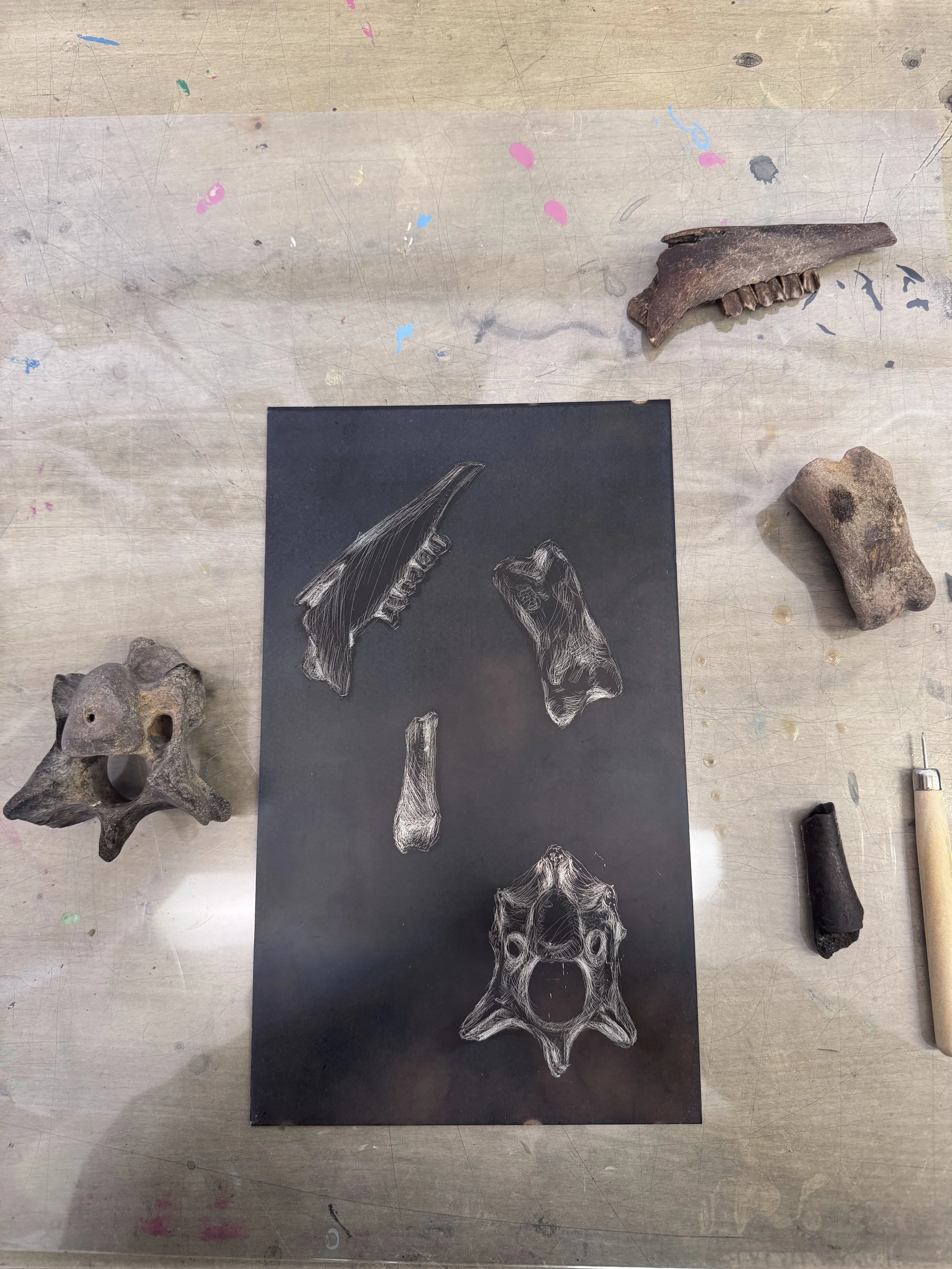

At my degree show, I presented my work across three forms — print, sculpture, and film — as a way to explore my central question about existence and the vitality of matter. These mediums allowed me to approach the same inquiry from different perspectives and scales, extending my understanding of how material can hold, transform, and communicate traces of life.

For the exhibition, I selected embossing prints, sculptures, and film to present a dialogue between surface and depth, presence and absence. In displaying my works, I considered not only the objects themselves but also how they occupy and activate space. I constructed two metal trays with thin legs to contain the artworks, compelling viewers to look down — an intentional gesture that evokes the act of mudlarking and the archaeology of fragments. This downward gaze encourages reflection on what lies beneath the surface — both materially and metaphorically.

The rough textures, fragmented forms, and organic surfaces of the works invite a sensory awareness of stillness and transformation. In Remains and Excavation, corroded zinc fragments resemble archaeological artefacts — remnants of a lost civilization — while simultaneously evoking natural formations such as fossils or river stones. This ambiguity between the human and geological creates a tension between the artificial and the organic, the ephemeral and the eternal. The accompanying film expands the experience, offering an immersive encounter that points towards continuity and future possibilities.

I intentionally arranged the installation within a quiet, minimal space, allowing light, shadow, and temperature to become part of the composition. These subtle environmental shifts animate the materials, giving them a sense of latent life. My aim was to create an atmosphere where viewers could contemplate time, decay, and continuity — an intimate encounter with the silent vitality of matter. In this way, my installations act as meditative environments, prompting reflection beyond the human scale and connecting the viewer to the slow rhythms of material existence.

Display my art work at degree show

Feedback and Public Engagement

Following the degree show, I have lots of feedback from the audience and my professor Paul, A lots of audience actually interested in the process and how I make the art work, In the future I will film the process to make it more understandable. I was encouraged to think more critically about selection and display — to be more deliberate about what to include or omit, and to refine the way my presentation communicates meaning. I realized that the arrangement of objects and the space between them are as important as the works themselves. Moving forward, I plan to be more selective, intentional, and conceptually precise in how I curate my installations, ensuring that every element contributes to the clarity and depth of the overall message.

Me explain my art work to public audience

Critical Reflection: Learning Through Making

Throughout Unit 3, my understanding of artistic creation has shifted dramatically. Initially, I viewed materials as tools to express ideas; now I see them as co-authors of meaning. This change required me to abandon control and embrace uncertainty — a process that was both liberating and challenging.

For example, when experimenting with casting techniques, I often failed to predict how the wax would behave. Sometimes the chemicals on the plate changes all the time or the wax overheated, yet those accidents produced the most interesting results. These moments taught me to recognise the intelligence of matter — a term Bennett uses to describe how materials “know” how to act within their own physical laws.

Zhuangzi writes that “Heaven and Earth and I are born together; all things and I are one.” This idea of unity extends into the studio: I am not separate from the materials but part of the same process of transformation. The artist, the object, and the environment form an assemblage of continuous interaction. In this sense, the creative act becomes an ethical practice — an exercise in humility, attentiveness, and respect for nonhuman forces.

Chemicals on the plate running

Overheated wax

Reflection on Relevant Artists

Simon Callery

During our artist talk with Simon Callery, I was immediately drawn to his deep connection with archaeology and his commitment to exploring material beyond the surface of the image. Like me, Callery is fascinated by how traces of history can be physically embedded in matter. He has worked closely with archaeologists on excavation sites, incorporating the soil, dust, and textures of the earth directly into his paintings. This process transforms the canvas into a physical object that records time, labour, and environment — rather than functioning merely as a flat pictorial surface.

What inspired me most was his act of cutting holes into the canvas. These openings disrupt traditional composition and invite viewers to consider space, depth, and the hidden layers of material. His concept of “physical painting” encouraged me to think beyond the visual, to treat surfaces as living entities that carry their own history. In my own work, I have adopted a similar approach — seeing materials not as passive carriers of ideas, but as active participants in the creative process. Callery’s practice showed me how art can operate like an excavation: a process of uncovering, revealing, and engaging directly with the vitality of matter.

Valentina D’Amaro, 1966

Orange Wallpit extended, 2016

Flat Painting Bodfari 14/15 Ferrous, 2015

Ben Nicholson

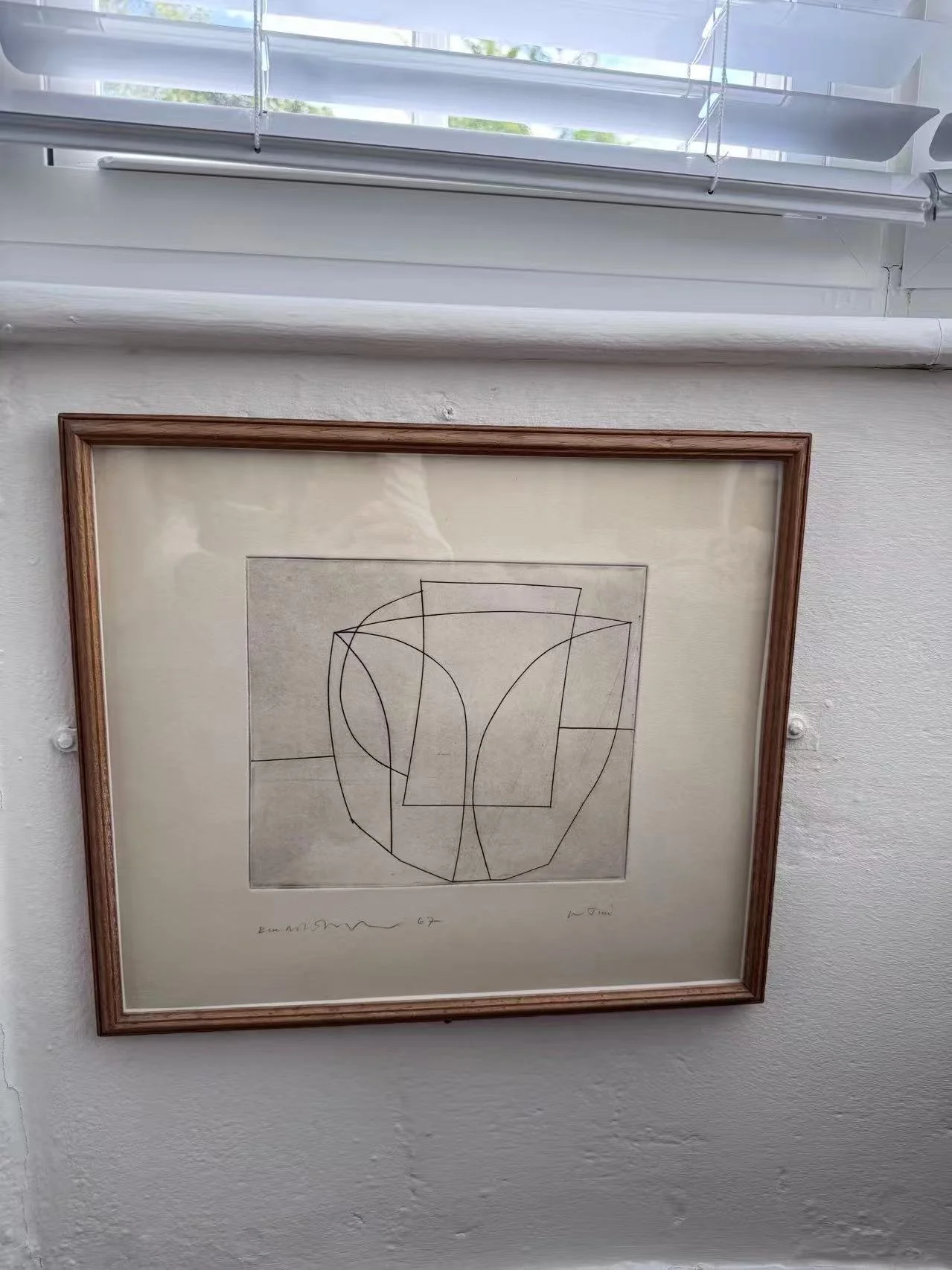

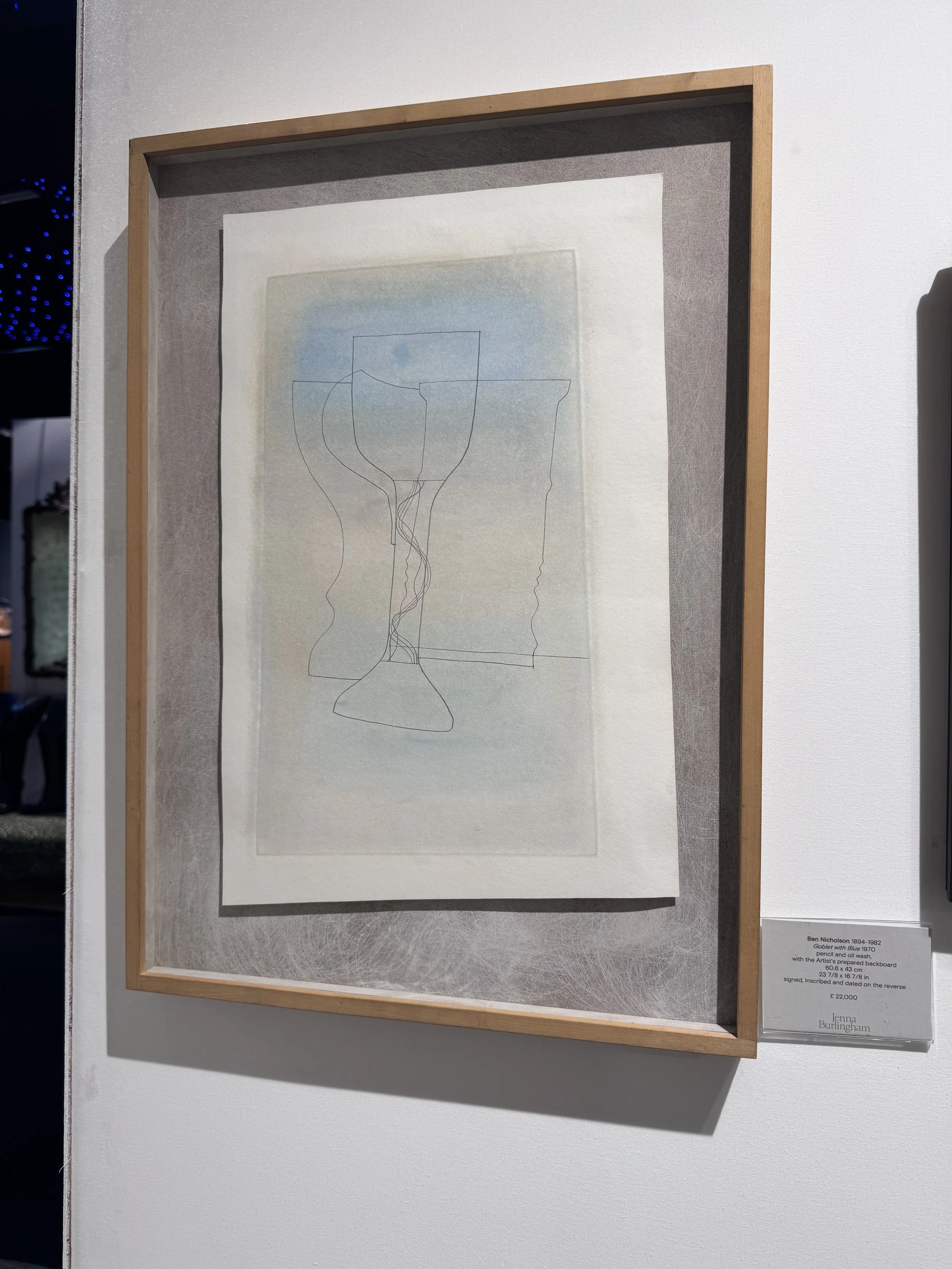

I first encountered Ben Nicholson’s work during my visit to Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge over the summer. Seeing his paintings and reliefs in person left a powerful impression on me. Nicholson’s minimalist yet poetic use of geometric forms, line, and collage resonated deeply with my own interest in simplicity and material essence. His works often combine order and spontaneity — precise shapes softened by texture, subtle layering, and tone.

I was particularly drawn to the way Nicholson used line to define space in such an understated yet expressive manner. The simplicity of his compositions creates a sense of quiet rhythm, much like natural forms that seem effortless but are full of underlying structure. His balance between abstraction and materiality has influenced how I approach form in my prints and sculptures. I became a true admirer of his ability to convey depth and emotion through restraint. From Nicholson, I learned that art can be powerful not through complexity, but through clarity and sensitivity — qualities I aim to express in my own work.

Ben Nicolson’s art work in kettle’s yard

Ben Nicolson’s art work in art fair

After being inspired by Simon Callery and Ben Nicholson, I became very interested in exploring shape and negative space. This led me to experiment with combining laser-cutting with printmaking. I used a laser-cut machine to cut shapes from the remains of my artwork — the zinc fragments left over after dissolving a large zinc plate. I then laser-cut Japanese paper into these shapes and applied them as chine-collé onto the print paper, while in some cases I even cut directly through the printing paper itself, creating layered and textured compositions.

Laser cut test out

Henry Moore

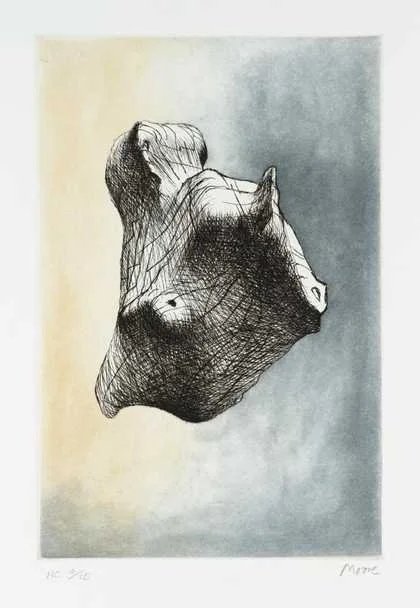

Among all the artists who have inspired me, Henry Moore has had the most profound influence. We share a fascination with natural forms — stones, shells, bones, and organic shapes — as sources of creative inspiration. Moore’s belief that nature offers infinite possibilities for abstraction has guided my own exploration of form and material. I discovered his book Henry Moore Prints and Portfolios in the library, which featured his sculptural studies and his printmaking practice.

Moore’s prints particularly fascinated me because they translate the weight and volume of his sculptures into two-dimensional form while retaining their organic vitality. I like his prints six stones, I like the contract he combine black drawing and soft background into one print, those stones become the subject and very important. I try to use different approach but have similar effect during my art practice.

His treatment of negative space, texture, and shadow made me reflect on how form can evoke life even when it is static. This connection between vitality, material, and transformation strongly relates to my own interests in Vibrant Matter and the vitality of inanimate objects. Inspired by Moore, I began creating multiple versions of my wax and bronze sculptures, experimenting with how form evolves under different conditions. His legacy continues to remind me that the essence of life can be found not only in living beings but also in the silent energy of materials themselves.

Six stones print

Stonehenge print

Oval with Points sculpture

I have always been inspired by Henry Moore’s Six Stones prints, which led me to experiment with creating a two-plate print of my own. I initially tested using boxing aquatint to create the shadows of bones on one plate while drawing the bones onto the other plate and printing them together, but the result was not ideal. I then tried image transfer on the shadow plate, which also did not achieve the effect I wanted. Currently, I am experimenting with photopolymer in hopes of capturing the desired result.

Inspired by Moore’s sculpture as well, I decided to explore negative space within organic forms. I tested making simple shapes using plaster based on the form of a bone, but I was not satisfied with the effect. Now, I am experimenting with creating a bone-shaped form within a stone-like shape, resembling a fossil, to achieve the interaction between organic structure and solid material that I am aiming for.

Print testing

Sculpture testing

Future Directions

Looking ahead, I plan to expand my exploration of material vitality through time-based media and interdisciplinary collaboration. I want to reach out to scientist and archaeologist to crate some prints or digital prints using microscope image and test some chemical reagent on to etching process. I am interested in incorporating print, sculpture, and film to make the transformation process more visible and multisensory. For example, making sculpture the stone shape with bones shape hollow inside like fossil and wax sculpture only cast a part of the shape.

Philosophically, I wish to continue bridging Eastern and Western thought — integrating Zhuangzi’s holistic cosmology with contemporary theories of new materialism. This cross-cultural approach not only reflects my personal background but also expands the discourse on how different traditions understand life, matter, and existence.

Fossil sculpture testing

Prints I have been working on

Stone image under a pocket microscope

Bone image under a pocket microscope

Soil image under a pocket microscope

Conclusion

Through my MA course, I have learned immensely—not only professional artistic skills but also valuable life lessons. It has truly been one of the greatest times of my life. I have met many inspiring people and exceptional professors who have guided and supported me throughout this journey. I am deeply grateful to all my classmates, and especially to Jo, Leo, Paul, Brian, and all the technicians for their generosity, patience, and expertise. They are an incredible team of professionals who have shown me the path toward becoming a professional artist.

During my studies, I developed my own artistic style and discovered my strengths, learning how to make the most of them. I’ve learned how to find inspiration and create coherent series of artworks using different materials, techniques, and approaches. As a printmaker, I have gained both technical proficiency and the creative freedom to experiment with processes and achieve unexpected results.

Beyond printmaking, I have explored film and sculpture, which helped me shape my own artistic language and gain a clearer vision of who I am as an artist. I also developed curatorial skills through various exhibitions and learned how essential communication and collaboration are in building connections within the art world.

After this experience, I truly feel ready to stand on my own as a professional artist, confident in my practice and my direction for the future. My future plan is to collaborate with archaeologists and scientists to continue exploring the ideas of new materialism and existence, while integrating both Western and Eastern philosophies to deepen my artistic inquiry.

Bibliography

Books

Renfrew, C. & Bahn, P., 2016. Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice. London: Thames & Hudson.

Ingold, T., 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F., 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Zhuangzi, 2003. Zhuangzi: Basic Writings. Translated by B. Watson. New York: Columbia University Press.

Khoroche, P., 2008. Nicholson. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd.

Schopenhauer, A., 1819. Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung.

Hirst, D., 2003. Romance in the Age of Uncertainty.

Jung, C.G., 1991. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Heidegger, M., 2018. Being and Time. London: Harper Perennial.

Harman, G., 2018. Object-Oriented Ontology. London: Penguin Books.

Parker, C. & Schlieker, A., 2022. Cornelia Parker. London: Tate Publishing.

Stewart, S., 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press.

Bennet, J., 2020. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bogost, I., 2012. Alien Phenomenology or What It’s Like to Be a Thing (Posthumanities). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Groys, B., 2017. Curating in the Post-Internet Age. e-flux journal, #94, October.

Hawkins, H. & Olsen, D. (eds), 2003. The Phantom Museum and Henry Wellcome’s Collection of Medical Curiosities. London: Profile Books.

Leslie, E., 2005. Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion Books.

Lilley, C., 2015. Materiality. London: MIT Press / Whitechapel Gallery.

Tsing, A.L., 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arp, E., Robertson, F. & Kröller-Müller Museum, n.d. The Poetry of Forms.

Mitchinson, D., 2010. Henry Moore: Prints and Portfolios. Switzerland: Patrick Gramer.

Lord, C., 2003. Figuring It Out. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Laozi, 1993. Tao Te Ching. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co, Inc.

Websites

Bourriaud, N., 2002. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Reel. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/94/219462/curating-in-the-post-internet-age/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Aldworth, S., n.d. Modern Alchemy: Towards a More Sustainable Chemistry. Available at: https://susanaldworth.com/exhibitions/modern-alchemy-towards-a-more-sustainable-chemistry/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Jones, K., n.d. About. Available at: https://katherine-jones.co.uk/about/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Tate, n.d. Jean Arp. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jean-arp-667 [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

National Geographic, n.d. Taoism. Available at: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/taoism/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Pace Gallery, n.d. Michal Rovner: Pragim, London. Available at: https://www.pacegallery.com/exhibitions/michal-rovner-pragim-london/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Videos

YouTube, 2021. [Sculptor - Henry Moore - Thames Television]. Available at: https://youtu.be/LrRc3sT2vXo?si=MKKHhKLsIaMM5iKO [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

YouTube, 2021. [Arp: Master of 20th Century Sculpture]. Available at: https://youtu.be/dkqJmMECZCs?si=EpQGqPtsAXDzyxcu [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

YouTube, 2021. [Jean (Hans) Arp]. Available at: https://youtu.be/CZN3fN1kWiw?si=3WWcDW2LhDizvvLu [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

YouTube, 2021. [Lord Colin Renfrew | Marija Redivia: DNA and Indo-European Origins]. Available at: https://youtu.be/pmv3J55bdZc?si=_zIh_xAnPdHIJTup [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].